Contents of this section:

Official admissions

Iran’s not-so-secret army

Funerals

Pilgrims or fighters?

Case study: The mysterious life and death Gen. Hassan Shateri

Notes & References

3. Iranian fighters

Like other aspects of Iranian involvement in Syria, the issue of Iranian fighters was initially denied by Iranian officials, then intermittently admitted and finally supported by the gradual emergence of undeniable evidence.

Official admissions

As mentioned above, one of the first official Iranian admissions of a physical presence on the ground in Syria was made by the deputy chief of Sepah Qods Ismail Qani: “If the Islamic Republic was not present in Syria, the massacre of people would have happened on a much larger scale,” he said in May 2012, shortly after the Houla massacre. “Before our presence in Syria, too many people were killed by the opposition but with the physical and non-physical presence of the Islamic Republic, big massacres in Syria were prevented.”241

About three months later, another senior Sepah Pasdaran commander offered another acknowledgement of direct military involvement in Syria: “Today we are involved in fighting every aspect of a war, a military one in Syria as well as a cultural one,” said the commander of Sepah Pasdaran’s Saheb al-Amr unit Gen. Salar Abnoush in August 2012, in a speech to volunteer trainees.242Of course Iranian officials could still claim, as they did, that ‘physical presence’ and fighting a ‘military war’ in Syria do not necessarily mean that Sepah Pasdaran had troops on the ground; it was only sending a number of commanders tasked with ‘advising’ and ‘training’ Syrian troops and commanders but they were not involved in the fighting themselves. However, a former Sepah Pasdaran commander told Reuters in February 2014 that these commanders (estimated to number between 60 and 70 high-ranking officers and many more lower-ranking ones) were “backed up by thousands of Iranian paramilitary Basij volunteer fighters as well as Arabic speakers including Shi’ites from Iraq.”243

Indeed, in June 2014, Brig. Gen. Hossein Hamedani, who is said to oversee Sepah’s operations in Syria, revealed that Basij forces had been “established in 14 Syrian provinces.”244 In an attempt to explain where all these fighters had come from, Hamedani claimed that 10,000 anti-Assad fighters had “switched sides” and were now Basij members. Sepah Pasdaran’s role in creating and training the NDF militias (which is presumably what Hamedani’s remarks refer to) has already been discussed above, and so has the recruitment of Iranian volunteers who want to go to fight in Syria.

In the same speech, which according to Iranian media was made during a memorial service in the Hamedan province attended by a number of Sepah Pasdaran commanders, Hamedani added that there are also 100,000 trained Iranian Basij fighters “who would like to go and fight in Syria” but “Iran does not need to send military staff to Syria yet.”245 And it is not just in Syria that the Iranian regime is setting up and training loyal paramilitary forces. “After Lebanon and Syria, a Basij force is now being formed in Iraq,” Hamedani said. “The Islamic Republic of Iran’s third child is born.”

The most direct admission of sending Iranian fighters to Syria came in early November 2013 from a member of the National Security and Foreign Policy Committee in the Iranian parliament. Speaking at an “anti-imperialist ceremony” in the region of Khorasan, Javad Karimi Qodousi said “there are hundreds of troops from Iran in Syria,” adding that what is often reported in the news as Syrian military victories is “in fact the victories of Iran.”246

The revelation was emphatically denied by Sepah Pasdaran, with the force’s spokesperson Ramazan Sharif saying: “We strongly deny the existence of Iranian troops in Syria. Iranian [commanders] are only in Syria to exchange experiences and advice, which is central to the defense of this country.”247 Clearly disturbed by the remarks, he added: “The media in Iran must show greater care when publishing this kind of news so that they do not aid the foreign media’s psychological warfare.”

It is worth noting that all the above admissions and revelations came from Iranian officials with demonstrable insider knowledge of Iranian military operations. As to why they were made, some appear to have been the result of competing interests or agendas within the regime (many were immediately removed from the websites that originally published them); others as signals or threats to the outside world. In some cases, though, they may have simply been boasting about the regime’s power and influence in front of regime supporters or the Iranian public more generally.

Iran’s not-so-secret army

In addition to these admissions and revelations, there have been dozens of pictures and videos of Iranian fighters posing with their weapons in different parts of Syria. For instance, in February 2014, Parsine news agency published images of an Iranian fighter posing with his gun and military uniform in Syria.248 Other pictures of the man show him using heavy weapons, standing next to Syrian military vehicles, at a Syrian military college or with groups of colleagues or children. According to the report, the man, who is described as a “religious eulogist” from Tehran, had gone to Syria to “defend holy Shia sites” in the country as part of a group calling itself “The Defenders of Sayyida Zaynab.” The same website had previously published images of another fighter, described as a “famous eulogist” from Tehran, who had also taken pictures of himself in Syria wearing a military uniform and pointing a gun.249 Both men and their colleagues appear to be ordinary fighters rather than commanders or advisors.

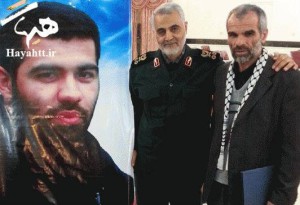

Gen. Qassem Soleimani standing next to the father of Rasoul Khalili, a member of the “The Defenders of Holy Shrines” who died in Syria in November 2013.

As a sign of the significance of this group(s) and its links to Sepah Pasdaran, Iranian media close to the force circulated in early 2014 a picture of Sepah Qods’s commander-in-chief Qassem Soleimani standing next to the father of a member of the “The Defenders of Holy Shrines” who had died in Syria.250 Mohammad Hassan Khalili, also known as Rasoul Khalili, was reportedly killed in battle in November 2013, having “voluntarily” travelled to Syria to “defend the Sayyida Zaynab shrine.” According to Bultan News, his 40th day ceremony was attended by Haj Agha Shirazi, Khamenei’s representative within Sepah Qods, as well as the force’s deputy chief Ismail Qani.251

As early as June 2012, the Free Syrian Army in Homs captured a group of Iranian snipers who had allegedly participated in suppressing the popular protests in the city dubbed “the capital of the revolution.” In a video posted on YouTube,252 the group’s leader, holding his Iranian ID card, says he is from the Iranian Armed Forces and that they had been taking instructions from the Syrian security services, particularly the Air Force Intelligence in Homs.

Less than two months later, in late August 2012, WSJ reported, quoting current and former members of Sepah Pasdaran, that the force had been sending “hundreds of rank-and-file members of Sepah Pasdaran and Basij… to Damascus,” in addition to higher-ranking Sepah commanders to “guide Syrian forces in battle strategy and Qods commanders to help with military intelligence.”253 According to the sources, many of these Iranian troops hail from Sepah units outside Tehran, particularly from Iran’s Azerbaijan and Kurdistan regions, where they “have experience dealing with ethnic separatist movements.” They were apparently sent to “replace low-ranking Syrian soldiers who have defected to the Syrian opposition,” the sources said, and they allegedly “mainly assume non-fighting roles such as guarding weapons caches and helping to run military bases.”

Iranian snipers captured by Syrian rebels in Homs in June 2012.

In October 2012, opposition activists filmed an Iranian Air Force-marked Ilyushin-76 airplane at Palmyra Airbase.254 The description accompanying the video says “dropping off troops to support Assad” but no troops can actually be seen in the short (30 second) video. Furthermore, the cameraman’s voice says “the content of the shipment is unknown.” Other similar videos of Iranian planes landing in various military airports in Syria have been posted online.255

The most conclusive evidence of Iranian fighters fighting in Syria was video footage, posted on YouTube in August 2013,256 seized by Syrian rebels (the Dawood Brigade) after overrunning a group of Iraqi and Iranian fighters from the Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas Brigade.

As mentioned before (in the ‘Training’ section), the footage was shot by an embedded Iranian filmmaker, Hadi Baghbani, who appears to have been making a special documentary about the Syrian adventure of a Sepah Qods commander called Ismail Haydari (Baghbani appears to have had unrestricted access to film everything). Both died in Syria at or around the same time on 20 August 2013, in what is believed to be the last scene shot by Baghbani’s camera near Aleppo. Some of the footage was broadcast in September 2013 by Al-Jazeera, the Netherlands Public Broadcasting network (NPO) and various other media outlets around the world. Two months later, the BBC made a 30-minute documentary based on the footage entitled Iran’s Secret Army.257

Most of the available footage is of Haydari talking about ‘working with’ Syrian regime troops and militias. One clip shows Iranian commanders instructing Syrian troops, and another shows an Iranian group of fighters, including the cameraman himself, involved in a gun battle against approaching rebels near a poultry farm in the suburbs of Aleppo.258 It is believed they were all killed there, where the rebels got hold of the camera and its footage.

Significantly, in one of the clips used in the BBC documentary, Haydari says: “This front [Syria] is supported by the Supreme Leader [Ayatollah Ali Khamenei] and [Hezbollah’s] Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah. On our side are lads from Iran, Hezbollah, Iraqi mujahideen [jihadis], Afghan mujahideen… The opponents are Israel, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar, UAE money, plus America, England, France and other Europeans…” He lists ‘Iranians’ among the other foreign militias fighting in Syria under Sepah Pasdaran’s control.

“One thing we do,” he later adds, “is to gather intelligence on an area. Then there are a few options: either we target the places [of] the rebels with artillery, or we target the routes they use with landmines and roadside bombs. And the third option is to do a commando raid…” He uses ‘we’ throughout.

BBC documentary about Sepah Pasdaran commanders and fighters in Syria, November 2013.

Funerals

As mentioned above, a prestigious, military-style funeral attended by many Sepah Pasdaran officers in military uniforms was held for Haydari and Baghbani in Iran, indicating both had a special position within the force. Yet, most Iranian state-controlled media reports on their death still insisted that Haydari was a ‘filmmaker’ and was in Syria to make a documentary, lumping his story with that of Baghbani. At least their death in Syria was acknowledged, for that of many other Iranian fighters and commanders who had reportedly died in Syria has not been (more on this in the ‘Iran’s Vietnam’ chapter).

Picture of two Sepah Pasdaran fighters, Mahdi Khorasani and Ali Asghar Shanaei, holding rifles in front of the Sayyida Zaynab shrine in Damascus, seen during their funeral in Iran in June 2013.

In June 2013, at least three Sepah Pasdaran members were announced to have been killed in Damascus while “defending the Sayyida Zaynab shrine.”259 The same rhetoric had been used by Hezbollah and the Iraqi militias when talking about their Syria fighters and martyrs, as discussed above. The funeral of Mahdi Khorasani and Ali Asghar Shanaei is believed to have been the first group funeral held in Iran for Iranians killed in Syria.260 The two were pictured together holding Kalashnikov-type rifles in front of the Sayyida Zaynab shrine.261 Another Sepah member whose funeral was held during the same month was Mohammed Hossein Atri, who Iranian media reports claimed was also killed while fighting near the shrine. His coffin was covered by numerous Sepah Pasdaran symbols.262 Others, such as Amir Reza Alizadeh, were reported to have been killed by bombs or during “clashes with terrorists.”263

The following month, Iranian media reported the death of another senior Iranian fighter who had also been ‘defending holy Shia shrines’ in Syria. Mehdi Moussavi was described by websites and blogs close to Sepah Pasdaran as a “Basij commander” in the Ahwaz region.264 A high-profile ceremony attended by senior Iranian officials was held for him at the Ahwaz airport in southern Iran, where his coffin arrived.265

In November 2013, Iranian media reported the death of Mohammad Jamali Paqal’a, who was killed in fighting in Syria.266 Mehr News Agency described him as a Sepah Qods commander and an Iran-Iraq war veteran who hailed from the same Sepah outfit that had trained General Qassem Soleimani.267

Interestingly, while doing its best to hide the news of its Syria dead from the outside world, Sepah Pasdaran often invited the public inside Iran to attend these funerals, which were often attended by Sepah members and representatives of the Iranian Supreme Leader.268 ‘Died while defending holy shrines’ also became a generic description for many of these ‘martyrs’.

Pilgrims or fighters?

If lying about someone after their death is easy, lying about them while they are still alive and in the hands of your enemy is much harder. In addition to the Iranian snipers mentioned above, Syrian opposition forces have frequently claimed they had captured Iranian fighters or members of Sepah Pasdaran in Syria, posting videos of their confessions and their documents online.269 The Iranian regime and its media outlets often claimed these were civilian pilgrims who had gone to Syria, despite the raging war, to visit Sayyida Zaynab and other holy Shia sites in the country.

In August 2012, 48 Iranian nationals were kidnapped by Syrian rebels on their way from Sayyida Zaynab to the Damascus airport. The rebels claimed they were all members of Sepah Pasdaran; the Iranian government claimed they were Shia pilgrims. Later on, however, Iran’s foreign minister added that some of them were “retired members” of Sepah Pasdaran and the army, while others were from “other ministries,”, but insisted that they were in Syria for pilgrimage.270

Statement of Al-Baraa Brigade on the failure of negotiations concerning the 48 Iranian captives, 4 October 2014.

Judging by the confessions of Iraqi militiamen (see above), both stories may in fact be true: fighters and low-ranking officers were often sent by land among groups of pilgrims and other visitors. Even if the Sepah members were retired, it is still likely that they were sent to Syria as advisors due to their experience.

In any case, the 48 Iranian captives were released in January 2013 in a prisoner exchange deal mediated by Turkey, in exchange for releasing 2,130 opposition detainees held by the Syrian regime.271 The move angered many regime supporters, many of whom posted angry comments on social media sites accusing the Syrian leadership of ‘not giving a toss’ about Syrian prisoners of war, while rushing to release so many ‘terrorists’ in exchange for a few Iranians.272 About a year later, a video posted by Syrian activists on YouTube showed a group of Syrian pro-regime prisoners of war wishing that they were Iranian or Hezbollah Lebanon fighters so that the Assad regime would hurry to negotiate their release in a similar prisoner exchange deal.273

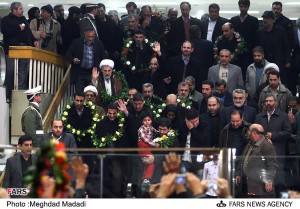

One of the high-profile official receptions held in Iran for 48 Iranian prisoners of war who were released by Syrian rebels in January 2013 in a prisoner exchange deal. The Iranian regime claimed they were ‘pilgrims’ but many turned out to be Sepah Pasdaran officers.

Angry reactions aside, the deal was perhaps a sign of who called the shots in Syria now. It was also an indication that the Iranian captives were of significance, as previous experiences show that the Iranian government does not care much about its ordinary citizens and even ordinary soldiers taken hostage.274 Indeed, their significance was obvious from the high-profile official delegations that met them upon their return to Iran. They included senior government officials and several key Sepah Pasdaran commanders, according to images published by Iranian media.275

Moreover, a number of Iranian opposition websites named at least four of the released hostages, describing them as current Sepah Pasdaran commanders from various Iranian provinces.276 These reportedly included a Brigadier-General 2nd Class who commands the Sepah Shohadaa unit in West Azerbaijan province; a Colonel who commands the 14th Imam Sadeq Operational Brigade in Bushehr; the Supreme Leader’s Representative at Sepah’s Orumiyeh unit; and an official from the 33rd al-Mahdi Brigade in Fars province.277 The Iranian regime nonetheless wanted everyone to believe that they were all in Syria in a personal capacity for religious pilgrimage.

Case study: The mysterious life and death Gen. Hassan Shateri

Gen. Hassan Shateri, the former head of the Iranian Commission for the Reconstruction of (South) Lebanon, who was killed in Syria in February 2013.

In February 2013, Iranian media reported the death of Hassan Shateri, the then head of the Iranian Commission for the Reconstruction of (South) Lebanon.278 Some Syrian opposition sources claimed he was shot by Syrian rebels as he was travelling from Aleppo to Beirut via Damascus.279 Others, including Israeli sources, claimed he had been killed in the Israeli air strike on 30 January, which apparently targeted a convoy carrying anti-aircraft missile systems bound for Lebanon.280 The Iranian regime also claimed Israel was behind the assassination and vowed revenge.281

However, available evidence does not seem to support the air strike story. Images published at the time of Shateri’s body being placed in its tomb in Iran show no burn marks or other injuries indicating an air strike.282 A “friend and colleague” of Shateri also stated on 8 March 2013 that he had seen Shateri’s gunshot wound before he was buried.283

In any case, it is clear that Shateri’s role went far beyond that of the head of the Lebanon Reconstruction Commission. In fact, it is widely known in Lebanon and Iran that the Commission is a cover for Sepah Qods activities there. While in Lebanon, Shateri operated under the alias of Hesam Khoshnevis, concealing his real identity even from the US Treasury Department, which added his alias to its sanctions list in August 2010 for “providing financial, material and technological support” to Hezbollah Lebanon.284

We now know that Shateri was a senior Sepah Pasdaran officer who had served in Afghanistan, Iraq and Lebanon. As an engineer, he was promoted in 1980s to head the force’s Sardasht headquarters and later the Hamzeh Seyyed al-Shohada Base combat engineering unit and Saheb al-Zaman engineering brigade.285 In 2006, he was picked to lead Iran’s ‘reconstruction’ efforts in South Lebanon following the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah. As a Fars News report put it, Shateri “went wherever he was needed by the Islamic Revolution.”286

Sepah Pasdaran’s chief Mohammad Ali Jafari and Sepah Qods’ chief Qassem Soleimani weeping at Shateri’s funeral in Tehran, 14 February 2013.

The prestigious funerals held for him in Tehran and Semnan on 14 and 15 February 2013, which were attended by the most senior officials of Sepah Pasdaran and the Iranian regime, were a clear sign of Shateri’s significance.287 Many of the attendees praised his “outstanding role in resistance against Israel” and described him as “no less than Imad Moghniyeh,” the Lebanese Hezbollah commander who was assassinated in Syria in 2008. Shateri’s coffin was covered with Lebanese Hezbollah flags and pictures of him in Sepah Pasdaran military uniform.288 Moreover, the news of his death was personally delivered to his family by the commander-in-chief of Sepah Qods Gen. Qassem Soleimani.289 Soleimani and Sepah Pasdaran’s chief Mohammad Ali Jafari were also photographed weeping at Shateri’s funeral in Tehran.290 A few days later, the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei invited Shateri’s family to his house to personally console them.291

The question is: what was Shateri doing in Syria, and in Aleppo specifically? Hours after his death, the Iranian embassies in Beirut and Damascus released information about Shateri’s destination in Syria and how he died. He had allegedly been in Aleppo to “research and implement development and construction projects” there, they said, and was killed by rebels on his way back to Lebanon.292 Later on, Iranian official statements and media reports omitted any mention of Aleppo and decided to go with the Israeli air strike story.

As a number of observers and experts have pointed out, the idea of a senior Sepah Qods commander going to a city that has almost fallen into the hands of the rebels and is extremely unsafe in order to look into construction projects is “nonsensical.”293 Moreover, it is unlikely that Gen. Soleimani would have sent “one of his top lieutenants” to Aleppo on a mission (accompanying an arms shipment to Hezbollah) that could have been done by a less senior operational commander.294

It is more likely, as American analyst Will Fulton has argued, that Shateri had been dispatched to lead a mission related to the Syrian chemical weapons and missiles facility in al-Sfeira, near Aleppo, which was at the time on the brink of falling into the hands of rebels.295 The facility is known to have had Iranian presence before and after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution (more on this in the next section). So it is reasonable to assume that Sepah Qods may have wanted to retrieve or destroy sensitive material or evidence on the site before it fell in the hands of the rebels.

Notes & References

241 A screenshot of the original interview in Persian with the Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA) is available here. For English, see: Saeed Kamali Dehghan, ‘Syrian army being aided by Iranian forces’, The Guardian, 28 May 2012.

242 A copy of the original report in the Iranian Students’ News Agency is available on Daneshjoo. For English, see: Farnaz Fassihi ‘Iran said to send troops to bolster Syria’, The Wall Street Journal, 27 August 2012.

243 Jonathan Saul and Parisa Hafezi, ‘Iran boosts military support in Syria to bolster Assad’, Reuters, 21 February 2014.

244 ‘General Hamedani’s most recent remarks on Syria’ (in Persian), ISNA, 29 June 2014. For English, see here.

245 Ibid.

246 ‘Sepah denies presence of “hundreds of Iranian troops in Syria”’ (in Persian), Deutsche Welle, 4 November 2013.

247 Ibid.

248 ‘New images and video footage of Iranian regime’s followers in Syria’ (in Persian), Parsine, 18 August 2013. For English, see here.

249 ‘Famous artist battles against rebels in Syria + Pictures’ (in Persian), Parsine, 26 June 2013.

250 e.g. ‘Soleimani taking pictures with father of Sepah member killed in Syria’, Digarban (in Persian). See also this report (in Persian). For English, see here.

251 ‘Pictures of the 40th day after martyrdom of Rasoul Khalili’ (in Persian), Bultan News, 30 December 2013.

252 ‘Arrest of Iranian snipers in Homs by Free Syrian Army’ (in Persian with Arabic subtitles), YouTube, 1 June 2012. A longer video without translation is available here.

253 Farnaz Fassihi, ‘Iran said to send troops to bolster Syria’, idem.

254 ‘Iranian Revolutionary Guard Transport IL76 TD at Palmyra Airport Syria’, YouTube, 22 October 2012.

255 See, for example, this video and this one.

256 Some of the raw footage, in six parts, is available on YouTube. There is apparently several hours of footage but only some of it has been posted online. For a detailed account of the story behind the footage, though the authors of this report do not agree with all the conclusions, see: Joanna Paraszczuk and Scott Lucas, ‘Syria Special Updated: Iran’s Military, Assad’s Shia Militias, & The Raw Videos’, EA WorldView, 15 September 2013.

257 Darius Bazargan, Iran’s Secret Army, BBC Our World, November 2013. The full documentary is available on YouTube.

258 Part 5 for the series referenced above .

259 For a list of publicly announced funerals around this time, see for example: Y. Mansharof, ‘Despite denials by Iranian regime, statements by Majlis member and reports in Iran indicate involvement of Iranian troops in Syria fighting’, The Middle East Media Research Institute, 4 December 2013.

260 Phillip Smyth, ‘Iran’s Losses In the “35th Province” (Syria), Part 1’, Jihadology, 14 June 2013.

261 The picture is available here.

262 See, for example, this picture.

263 ‘Body of Martyr Amir Reza Alizadeh buried in Rudsar’ Mehr News Agency (in Persian).

264 See for example, this report (in Persian).

265 ‘Funeral of martyr Sayyid Mahdi Mousavi’ (in Persian), ISNA Khouzestan, 8 July 2013.

266 See, for example, this Mehr News report (in Persian).

267 Ibid.

268 In addition to the above, see for example this report (in Persian).

269 e.g. Video from February 2012; Video from February 2012; Video from February 2012; Video from April 2012; Video from June 2012; Video from October 2012; Video from October 2012; Video from March 2013; Video from April 2013; Video from September 2013; Video from February 2014.

270 ‘‘Retired’ Revolutionary Guards among Syrian hostages: Iran’, Al-Arabiya, 8 August 2012.

271 ‘Syrian government frees 2,130 prisoners in exchange for 48 Iranians’, CNN, 10 January 2013.

272 See, for example, this Orient TV report (in Arabic).

273 ‘Assad regime captives held by the Free Army envy Iranians’ (in Arabic), YouTube, 11 February 2014. For English, see here.

274 See, for example: ‘Petty lives of soldiers, precious lives of commanders’, Naame Shaam, 27 March 2014.

275 See, for example, e.g. this picture and this picture published by Fars News.

276 Farnaz Fassihi, ‘Iran said to send troops to bolster Syria’, idem.

277 For more details, see: Will Fulton, ‘IRGC Shows Its (True) Hand in Syria’, Iran Tracker, 14 January 2013.

278 See, for example, ‘Martyrdom of president of Commission for Reconstruction of Lebanon at the hands of Zionist regime agents’ (in Persian), Ahlul-Bayt News Agency (ABNA), 13 February 2013.

279 Saeed Kamali Dehghan,‘Elite Iranian general assassinated near Syria-Lebanon border’, The Guardian, 14 February 2013.

280 Elior Levy, ‘Rebels: Iranian official killed in airstrike on Syria’, YNet News, 14 February 2013.

281 See for example here and here.

282 ‘Picture / the moment that Shateri kissed the Supreme Leader’s hand’ (in Persian), ABNA, 15 February 2013. The pictures appear to have been removed since.

283 ‘Ceremony to commemorate martyr Shateri held in Qom’ (in Persian), ABNA, 9 March 2013. For more details, see: Will Fulton, ‘The assassination of Iranian Quds Force General Hassan Shateri in Syria’, Iran Tracker, 28 February 2013.

284 US Treasury Department, ‘Fact Sheet: U.S. Treasury Department Targets Iran’s Support for Terrorism’, 3 August 2010.

285 For more on Shateri’s career, see for example: Farnaz Fassihi, ‘As Iran buries general, Syria rebels say he was killed in Israeli strike’, The Wall Street Journal, 15 February 2013. For his position within Sepah Qods’s global network, see for example this illustration.

286 ‘Martyr Shateri went wherever he was need by the Islamic Revolution’ (in Persian), Fars News, 21 February 2013.

287 See, for example, these news reports (in Persian): 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

288 See, for example, this picture.

289 ‘Representative of the Supreme Leader: We will quickly take revenge from Israel for Martyr Shateri’ (in Persian), ARNA News, 16 February 2013.

290 ‘Two commanders in grief’ (in Persian), Afsaran, 14 February 2013.

291 ‘Family of martyr Gen. Shateri [received by] the Great Leader of the Revolution’ (in Persian), ABNA, 19 February 2013.

292 ‘Iranian embassy in Lebanon informs of the martyrdom of the head of the Iranian Commission for the Reconstruction of Southern Lebanon’ (in Persian), IRNA, 14 February 2013; ‘Reflection by world media on the martyrdom of Hassan Shateri’ (in Persian), Javan, 16 February 2013.

293 Will Fulton, ‘The assassination of Iranian Quds Force General Hassan Shateri in Syria’, idem.

294 Ibid.

295 Ibid.

English

English  فارسی

فارسی  العربية

العربية