Contents of this chapter:

Contents of this chapter:

At any cost

‘Eat just once a day or fast’

Iran’s ‘resistance economy’

Counting the dead

Bleeding Iran in Syria

How long can the Iranian regime bleed?

Notes & References

III. Iran’s Vietnam

Most observers today agree that the Iranian regime’s adventure in Syria is costing it a great deal – politically, economically and even socially. Indeed, many have started using the term ‘Iran’s Vietnam’ (in reference to the catastrophic consequences of the Vietnam war for the US) to describe the ‘Syrian swamp’ in which the Iranian regime appears to be slowly drowning.1 This chapter will shed some light on two main aspects of this ‘Syrian Vietnam’, namely the economic and human costs to Iran of the war in Syria and how it is impacting on the Iranian economy and ordinary Iranians.

While it may be obvious that the Iranian regime has made a choice to ‘go for it’ in Syria at any cost, this Syrian Vietnam is not just a consequence of this choice. It is also a deliberate policy by the US administration and its allies, which we describe here as a strategy of ‘bleeding Iran in Syria.’ The chapter will examine and assess this strategy and will argue that this ‘slow bleeding’ policy is being implemented at the disproportionate expense of the people of Syria and the wider region, and will inevitably lead to more instability and extremism in the region and beyond. In other words, we will argue that Western hopes that a proxy war with the Iranian regime in Syria, coupled with economic sanctions, would eventually lead to the weakening and even collapse of the Iranian regime (‘winning the Syria war in the streets of Tehran’) are, at best, wishful thinking.

At any cost

After three and a half years of war, the Syrian economy is unsurprisingly in a state of acute distress. The full extent of economic losses are difficult to measure since the Syrian government has stopped gathering and releasing any meaningful statistics since 2011. Nevertheless, unofficial estimates indicate that Syria’s gross domestic product (GDP) has dropped by at least 40-50 per cent during 2011-2013, with an estimated loss of 145 billion US dollars.2

Yet the Syrian regime has not collapsed economically, as many analysts were expecting it to do, basing their analysis on the experience of Iraq in the wake of the US invasion in 2003, among other examples. And that is mainly thanks to the Iranian regime, and to a lesser extent to Russia and China, which have been propping up the Syrian regime over the past three and a half years.

Chapter I examined in considerable detail the Iranian regime’s military involvement in Syria. In addition to Iranian commanders and fighters, there are also all the pro-regime militias fighting in Syria, which have been largely controlled and financed by Sepah Pasdaran. This includes the Syrian shabbiha and National Defence Forces (NDF). According to Iranian officials and commanders themselves, the NDF has some 70,000 members. They are not volunteers, however, as these officials often describe them. They are, rather, mercenaries who receive regular salaries and financial rewards, as many of them have confessed (see chapter I).

The monthly salary of a normal NDF member is said to range between 15,000 and 25,000 Syrian pounds (100 to 160 US dollars). Multiply that by 70,000 and you will get a rough idea of how much this force alone is costing the Syrian and Iranian regimes every month. According to one regime defector, their salaries are paid through a “slush fund replenished with US dollars flown in from Iran.”3 A US Treasury sanctions designation in December 2012 claimed that the Iranian regime was providing the NDF with “routine funding worth millions of dollars.”4

Then there are all Iranian-backed Iraqi militias fighting in Syria. At least fighters from ‘Asa’eb Ahl al-Haq are known to be paid 500 dollars a month, according to confessions of Iraqi militiamen captured by Syrian rebels.5 The money is allegedly sent to them through Iraq by the militia’s leader Sheikh Qais al-Khaz’ali, who is said to be based in Iran. Similarly, Afghan fighters are being offered 500 US dollars a month by Sepah Pasdaran to fight in Syria on the regime’s side.6

With regard to Hezbollah Lebanon, the force is known to have been receiving at least 100 million US dollars per year from the Iranian regime in supplies and weaponry, according to US estimates.7 Then there are all the running costs of the Syria operations, which are likely to be paid for by the Iranian regime too (food, training, transport, fuel, etc.). Add to that the militiamen’s salaries and the money offered to the families of those killed in battle. In early 2014, Naame Shaam’s correspondent in southern Lebanon was told by a number of families of Hezbollah members who had died in Syria that “the prize of martyrdom in Syria” was $50,000 for each young and unmarried fighter. The families of older men with children are apparently paid even more, and orphaned children are supported by Hezbollah for years.8

The weapons used by these fighters also cost money. As detailed in chapter I, Iranian weapons have been shipped to Syria, despite a UN embargo, since the start of the war. In March 2013, Reuters described this as a “weapons lifeline to al-Assad.”9 But in addition to Iranian weapons, Tehran has reportedly also been footing the bill for at least some of the Russian weapons supplied to the Syrian regime.

A quick look at available estimates of the Syrian regime’s known stocks of weapons shows an increase in most types of weapons.10 Most appear to be Russian-made and many are believed to be paid for by Iran. For instance, according to Russian newspapers, part of the MiG aircraft deal between Russia and Syria was financed by Iran as “a back-door purchase” of similar aircraft by Iran (to circumvent sanctions).11 No further details are known owing to the secrecy surrounding such deals. As David Butter, an associate fellow at Chatham House, put it in September 2013, “Syria has never paid for its weapons from Russia – it doesn’t have any money… There is a pipeline of resupply of weapons going from Russia to Syria, possibly with Iran involved in that, but it’s pretty obscure.”12

The Syrian regime’s economic ‘resilience’ is most obvious in loyalist areas in Syria. Despite three years of war and economic decline, most areas under regime control continue to enjoy a good level of provision of many of their basic needs and services, such as water, electricity, fuel, food supplies and so on. The regime has even been able to pay the salaries of most state employees in these areas, not to mention those of soldiers and militia fighters.

The answer to this apparent puzzle lies in another aspect of ‘help’ offered by Iran to the Syrian regime: financial loans and credit lines.

Iran deposited $500 million in Syria’s Central Bank vaults in January 2013 to prop up the Syrian pound, which was on the brink of crashing. The Syrian regime has also been borrowing 500 million US dollars a month from Iran.

As early as July 2011, media reports revealed that Iran was considering offering the Syrian regime financial assistance worth 5.8 billion US dollars in the form of cash and oil supplies. According to French business daily Les Echos, citing a confidential report by a think-tank linked to Iran’s Supreme Leader called the Strategic Research Center, the plan was approved by Khamenei himself.13 The offer reportedly included a three-month loan worth 1.5 billion US dollars to be made available immediately. Iran would also provide Syria with 290,000 barrels of oil every day over the following month, the report said.

In January 2013, Iran deposited 500 million US dollars in Syria’s Central Bank vaults to prop up the Syrian pound, which was on the brink of crashing. In July 2013, Tehran granted Damascus two credit lines worth 4.6 billion US dollars. The first, worth 1 billion US dollars, was intended to fund imports. The second, worth 3.6 billion US dollars, was dedicated to the procurement of oil products. In return, Iran would acquire equity stakes in investments in Syria.14

In an interview with the Financial Times in June 2013, Qadri Jamil, then Deputy Prime Minister for the economy, said that Syria actually had “an unlimited credit line with Tehran for food and oil-product imports,” adding that his government was borrowing 500 million US dollars a month.15 A Syrian government consultant confirmed this in another interview in July 2013.16

As to how these credit facilities were used, Syrian Minister of Oil Suleiman Al-Abbas provided a clue when he announced, in December 2013, that three Iranian oil tankers were docking in Syrian ports every month, paid for by the Iranian oil credit line. Around the same time, the Syrian General Foreign Trade Organization also issued two tenders to buy large quantities of food products, such as flour, sugar and rice, to be paid for through the other Iranian credit line (meaning sellers had to accept payment through Iranian funds under an agreement between the Commercial Bank of Syria and the Export Development Bank of Iran).17 Mostly Iranian companies, offering food products “available inside Iran,” took part in both tenders. In April 2014, Iran shipped 30,000 tonnes of food supplies to Syria to “help the Syrian government deal with shortages.”18

Iran shipped 30,000 tons of food supplies to Syria in April 2014 to “help the Syrian government deal with shortages.”

Needless to say, none of this food made its way to the people who need it most: people in destroyed or besieged areas. It may also be interesting to compare the above-mentioned amounts to the level of bilateral trade between Syria and Iran before the current war, which stood at 316 million US dollars in 2010, according to official Syrian statistics.19

In addition to money to buy (Iranian) food and oil, the Iranian regime has also been helping the Syrian regime get cheep oil from elsewhere, mainly for military purposes (diesel for military vehicles, etc.). An investigation by Reuters in December 2013 revealed that “millions of barrels” of Iraqi crude oil had been delivered that year, under the radar, to the Syrian regime through Lebanese and Egyptian trading companies, on board Iranian ships.20 The investigation, based on an examination of previously undisclosed shipping and payment documents, said these previously unknown shipments, in addition to more known ones of Iranian crude oil, kept the Assad armed forces “running” in spite of the international sanctions.

Three Iranian oil tankers have been docking in Syrian ports every month, paid for by an Iranian oil credit line.

Syria has lost almost all its oil exports, primarily because the regime surrendered or handed over the main oil wells in Syria to Islamist armed groups. So it has been depending mostly on Iran for its fuel needs, in addition to buying some oil from these Islamist groups, as detailed in chapter I.

So how much exactly has the Iranian regime spent on its Syria adventure so far, and where is this money coming from?

In August 2013, French newspaper Libération reported, citing the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies as a source, that Iran had already “wasted around 17 billion dollars of its foreign currency reserves” on the war in Syria.21 Other sources estimate that the Iranian military efforts in Syria are costing about 1.5 billion US dollars per month.22 But how are these estimates calculated? And do they include all the aspects mentioned above?

An obvious place to start looking is military expenditure databases. However, the data on Iran in most of these databases is often not only unreliable or unavailable (owing to Iran’s secrecy regarding its military activities), it also does not include spending on paramilitary forces. For instance, the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s Military Expenditure Database states in a footnote: “The figures for Iran do not include spending on paramilitary forces such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).”23 Given that this force, Sepah Pasdaran, and its external arm Sepah Qods are the ones that are in charge of most of the Syria operations (save for some technical assistance provided by the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and the Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics, as indicated in chapter I), such databases are of little use for our purposes.

Sepah Pasdaran’s declared budget is allocated by the Iranian government every year and must be approved by parliament, like all other government spending. The budget allocated to the force this year was just over 44 trillion Iranian rials (around 1.7 billion US dollars), a 30 per cent increase compared to the year before.24 Sepah’s budget has been constantly increasing in the last few years, which is presumably to do with the force’s adventures in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere. As to how this money is divided within the force (e.g. how much goes to Sepah Qods and external operations), that is a well-guarded secret.

To put things in perspective, 44 trillion Iranian rials is nearly equivalent to the budgets allocated to health and education combined. The health budget for the current year is 25 trillion rials and the education budget is 21 trillion.25

In addition to the official budget allocated by the government, eight per cent of Iran’s infrastructure budget also goes to Sepah Pasdaran. This is, in fact, only what is publicly announced; in reality it may be as high as 60 per cent. Sepah or its affiliates are often the sole winners of the most profitable construction and oil-related contracts in Iran. The force also controls much of the import-export industry and has a monopoly over many other vital economic sectors in the country. Nonetheless, the force is not subject to the Iranian tax law.

Like Sepah, the Supreme Leader also controls a massive economic empire known as Setad, or the Setad Ejraiye Farmane Hazrate Emam (Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam). Setad manages and sells properties ‘abandoned’ or expropriated mainly from members of the opposition. The company’s holdings of real estate, corporate stakes and other assets are estimated to be worth about 95 billion US dollars, according to calculations by Reuters in November 2013.26

Finally, there are also many foundations and businesses affiliated with or close to Sepah and Khamenei, many of which are known to give generous ‘donations’ to the force. There is no space here to look into this but it is worth mentioning in the context of who is funding the Iranian regime’s adventure in Syria and how Iranian public and private money is being wasted.

‘Eat just once a day or fast’

The impact of the war in Syria on the Iranian economy and ordinary Iranians cannot be separated from that of the international sanctions on Iran and Iran’s nuclear programme. There are intrinsic reasons for this.

The main reason for the Iranian regime’s uncompromising determination to save Bashar al-Assad’s regime at any cost is to maintain its ability to ship arms to Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza via Syria, so as to keep these strong deterrents against any possible Israeli and/or Western attacks on Iran’s nuclear facilities. Together, these two ‘lines of defence’ (Hezbollah and Hamas and the nuclear bomb) are meant to secure the Iranian regime’s survival. If the Assad regime falls, Iranian arms shipments to Hezbollah are likely to stop and Hezbollah would no longer be the threatening deterrence against Israel that it is now. The Iranian regime would therefore feel more vulnerable and would not be able to negotiate from a strong position during nuclear talks with the E3+3 powers in Vienna and Geneva, as it is doing now. It may even have to give up its nuclear dreams for a while. All available resources (human, economic, military) must therefore be mobilised to achieve this strategic aim.

Thus, if we add all the above costs (hundreds of billions of dollars) to the costs of Iran’s nuclear programme (which is estimated to have cost well over 100 billion US dollars so far 27) and the costs of the sanctions imposed on Iran because of the nuclear programme (which are estimated to be around 100 million US dollars each day 28), the burdens on the Iranian economy are enormous.

One indicator of the this economic burden is the inflation rate, which has more than tripled in the last five years (from 10 per cent in 2009 to over 30 per cent in 2014) and has increased by about 10 per cent since the start of the war in Syria.29 Official reports also indicate that Iranian household purchasing power has decreased by about 25 per cent. A price list of basic food items published by BBC Persian in March 2014 showed that consumer prices in Iran had at least tripled in the past four or five years.30 According to the Ministry of the Economy, in July 2014, almost a third of all families in Iran (31 per cent) lived below the poverty line.31 Three months before, in March 2014, Iranian MP Mousareza Servati said 15 million Iranians (about 20 per cent of the population) were living below the national poverty line. Seven million of them were not receiving assistance of any kind.32

Despite Iranian media’s celebration of President Hassan Rouhani’s economic ‘achievements’,33 the reality is that Iran’s economic problems are unlikely to go away any time soon unless there are fundamental shifts in its foreign policies. And that is certainly not in the president’s power. The same applies to Hezbollah Lebanon.34

In March 2014, The New York Times published an article entitled “Hopes fade for surge in the economy.”35 The article argued that people in Iran had voted for President Rouhani in the hope for a revival of the country’s ailing economy. But more than six months after he took office, “hopes of a quick economic recovery are fading, while economists say the government is running out of cash.”

On taking office, he discovered that the government’s finances were in far worse condition than his predecessor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, had ever let on. Now, with a lack of petrodollars and declining tax revenues, Mr. Rouhani has little option but to take steps that in the short-run will only increase the pain for the voters who put him into office.36

The article also quotes Saeed Laylaz, an economist and an advisor to President Rouhani, saying Iran is heading to a “black spring” and only a “miracle” could save it from political damage caused by the economic problems. “I am worried we might witness turmoil,” he added.

But is it true, as this and other media reports claim, that Iran is so short of cash that the government has “no other option” but to take “painful steps” such as printing money (therefore pushing inflation further up) and cutting down on public spending? While phasing out energy subsidies, Iran has been sending millions of barrels of oil to Syria at discount prices, paid for by Iranian credit, as indicated above. While winding down social assistance payments to nearly 60 million poor Iranians (about 12 US dollars a month), Iran has been sending millions of tonnes of food and cash to Syria. It just doesn’t make sense, as more and more Iranians are starting to realise.

It is worth noting that Iranian officials generally tend to avoid blaming the sanctions or Iran’s foreign policy for economic hardship, as that might be interpreted as a victory for the West. Instead, they often focus on mismanagement, corruption and ‘unwise management’. Not that this is not true too.37

Iran’s ‘resistance economy’

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei wearing worn-out sandals, in a symbolic message that the Supreme Leader is ‘suffering’ like poor Iranians and he expects everybody to do the same – March 2014.

In February 2014, Ayatollah Khamenei renewed his call to implement a “parallel economic plan” that he had first announced in 2010, which he dubbed “resistance economy.”38 Based on the principle “self-sufficiency,” the plan is an attempt to thwart the impact of the sanctions. The Supreme Leader promised that his strategy would “lead to welfare and improving the condition of the life of all the people, especially the poor.” Except it didn’t. Rouhani nonetheless “endorsed” the plan and wrote to various government institutions urging them to implement it.39

Meanwhile, as Iran’s economy ‘deteriorated’ further and the new government proved unable to solve the country’s ‘chronic’ financial problems, Iranian officials seemed to raise the tone of their warnings to the Iranian public that things will only get worse, clearly preparing them for more inflation and more poverty and hardship. Here are a few examples:

∙ In March 2014, Ali Fallahian, a member of Iran’s Assembly of Experts and a former intelligence minister who is most famous for killing Iranian intellectuals in the 1990s, defied the Western sanctions and said, if they got harsher, “we will eat just once a day or fast.”40

∙ A few days before, Ali Saidi, Khamenei’s representative at Sepah Pasdaran in the Ahwaz region, had said: “We are heading toward many challenges and sanctions, but we are not going to give up what we have achieved with blood only to get some bread. The people of Iran should prepare themselves for more suffering.”41

∙ In that same month, Iranian state-controlled media published pictures of Ayatollah Khamenei wearing worn-out sandals, in a symbolic message that the Supreme Leader is ‘suffering’ like poor Iranians and he expects everybody to do the same.42

Counting the dead

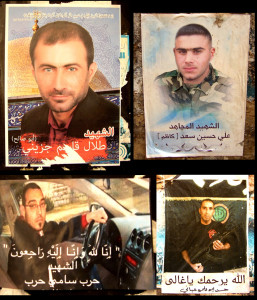

Chapter I cited many examples of Sepah Pasdaran, Hezbollah Lebanon and Iraqi militia commanders and fighters killed in Syria and the official funerals held for them in Iran, Lebanon and Iraq respectively. A number of websites and blogs have collected pictures and videos of these funerals, along with their owners’ names and stories.43

Both Sepah Pasdaran and Hezbollah Lebanon have been very cagey about their casualties in Syria from the beginning.

However, most of the Iranian and Lebanese funerals referred to above were for senior Sepah and Hezbollah commanders. Funerals for ordinary fighters were either held in secret or not held at all. This makes the task of assessing Sepah’s and Hezbollah’s losses in Syria very difficult, if not impossible.

In August 2014, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said it had documented the death of 561 Hezbollah Lebanon fighters in Syria. The number of deaths from other Shia militias documented by the organisation was 1,854.44 However, as the report points out, the real figures are likely to be much higher as a result of the secrecy surrounding most of these forces’ casualties.

Following the publication of some of the above-referenced reports and the issue of Hezbollah Lebanon’s involvement in Syria and its mounting casualties there becoming a hot topic, the party reportedly started to ‘bribe’ the families of its ‘martyrs’ – allegedly offering them between 20,000 and 25,000 US dollars, according to some media reports – if they accepted not to announce the death in public and not to hold a public burial ceremony.45 Some funerals may have also been kept low-key and not publicised online, making it difficult for outside observers and researchers to document them.46

Naame Shaam’s correspondent in Beirut toured several predominately Shia districts in the Lebanese capital in April 2014. In one area, near the ‘Amiliyeh school, within just 20 meters he saw posters of three Hezbollah and one Amal ‘martyrs’ who had died in Syria.

In March 2014, a Lebanese poll found that more than 70 per cent of the 600 participants queried, who were all residents of al-Dahiyeh, Beirut – a Hezbollah stronghold – knew someone (from their family, neighbourhood or village) who had been killed in Syria.47 In April 2014, Naame Shaam’s correspondent in Beirut conducted a short tour of several predominately Shia districts in the Lebanese capital. In one area alone (near the ‘Amiliyeh school), within approximately 20 metres he saw posters of one Amal and three Hezbollah ‘martyrs’ who had died in Syria.48

The number of Hezbollah fighters who have died in Syria since March 2011 is certainly higher than that publicly admitted by the party (a few hundred, at best). In the al-Qusayr battle alone, well over 100 Hezbollah fighters were killed, according to Syria opposition sources, of whom some 100 were confirmed by Hezbollah (see chapter I). In the Yabroud battle, at least as many were killed, if not more.49 In one week alone, Hezbollah held an official funeral for 56 of its fighters killed in Yabroud after their bodies were returned to Lebanon.

Moreover, many corpses were not retrieved, according to Syrian and Lebanese sources.50 In April 2014, a Free Syrian Army commander was quoted by Al-Hayat newspaper saying:

A big number of [corpses of] Hezbollah members who were killed in al-Qusayr are still in corpse refrigerators and Hezbollah cannot take them out. It is important to distinguish between the Shia and Hezbollah, because many honourable [Shiites] are opposed to Hezbollah and strongly refuse to send their sons to participate in the killing of the Syrian people. So the party [Hezbollah] has found itself in a trap. Families [of martyrs] are told their sons are in Southern Lebanon, at the border with Israel. That’s why there are more than 175 corpses in refrigerators in Hasbayya since the Qusayr battle, and the party cannot tell their families about them.51

Both Sepah Pasdaran and Hezbollah Lebanon have been very cagey about their casualties in Syria, right from the start. Both have been doing all they can to keep this information hidden from the public because it could show how heavily involved they are in the war there. It would also reveal how much they are losing, which could be damaging to the morale of their supporters. Suppressing such evidence is a classic war tactic aimed at avoiding public pressure demanding to ‘bring the boys back home’ before they too die out there.

Bleeding Iran in Syria

In the wake of the Ghouta chemical massacre in August 2013, US President Barak Obama threatened to use military force to punish the Syrian regime for crossing his famous ‘red line’, only to seize on an offer by Russia whereby Syria would dismantle and surrender its chemical weapons stockpile to avoid the attack. The deal surprised and disappointed many people around the world. Yet, portraying Obama as a reluctant, indecisive president who is lacking a strategy on Syria, as numerous media reports and commentaries have been doing, seems to miss an important point.

It may be true that the US and its Western allies have so far not been willing to intervene in Syria in any decisive manner. But that has not been out indecisiveness. Rather, Obama and his team appear to have adopted a policy of ‘slowly bleeding Iran and Hezbollah in Syria’ – that is, arming Syrian rebels just enough not to lose the war, but not to win either. A prolonged fight in Syria, according to this rationale, would not only weaken the Syrian army so that it is no longer a threat to Israel, both directly and indirectly, it would also significantly weaken the Iranian regime and Hezbollah Lebanon. Coupled with prolonged economic sanctions against Iran, this may eventually lead to the collapse of the Iranian regime, or at least weaken it to the point that it is no longer a threat and can be easily forced to comply with US agendas.

A report by The New York Times from October 2013, based on interviews with dozens of current and former members of the US administration, foreign diplomats and Congressmen, sheds some light on the reasoning behind the Obama administration’s position on Syria.52 According to the report, three of Obama’s closest aides, who are said to have his ear on Syria, are all against direct military intervention in the country: Denis McDonough, the White House chief of staff and a former deputy national security adviser, Tom Donilon, Obama’s former national security adviser, and Susan Rice, the US ambassador to the United Nations.

During a day trip with a group of senior lawmakers to the Guantánamo Bay naval base in early June 2013, McDonough reportedly argued that the status quo in Syria could “keep Iran pinned down for years.” In later discussions, he also suggested that a fight in Syria between Hezbollah and al-Qaeda would “work to America’s advantage.” The following month, Obama asked Rice, who had succeeded Donilon as national security adviser, to undertake a review of American policy in the Middle East and North Africa and to “make Syria part of a broader strategy involving both Iran and the Middle East peace process.”

The strategy was made clear by President Obama himself during a long interview about Israel and Palestine in March 2014:

I’m always darkly amused by this notion that somehow Iran has won in Syria. I mean, you hear sometimes people saying, ‘They’re winning in Syria’. And you say, ‘This was their one friend in the Arab world, a member of the Arab League, and it is now in rubble’. It’s bleeding them because they’re having to send in billions of dollars. Their key proxy, Hezbollah, which had a very comfortable and powerful perch in Lebanon, now finds itself attacked by Sunni extremists. This isn’t good for Iran. They’re losing as much as anybody. The Russians find their one friend in the region in rubble and delegitimized.53

As a number of commentators observed at the time, the implication here is that Obama and his team “could be seeking to intentionally prolong the war, despite the catastrophic scale of the death and destruction that is taking place as a result, because it is bad for Iran and Russia.”54

The President even “rebuffed” a detailed plan, presented to him in summer 2012 by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and then CIA Director David Petraeus, to arm and train Syrian rebels.55 After Petraeus resigned, his successor Michael J. Morell renewed his predecessor’s pitch to arm the rebels; Obama was still not convinced, despite new intelligence assessments warning that Syrian regime forces and militias were gaining the upper hand in the war, thanks largely to Iranian munitions shipments that had “replenished the stocks of [Syrian] army units,” while the rebels were running out of ammunition and supplies.

By now, the debate had “shifted from whether to arm Syrian rebels to how to do it,” according to the above-mentioned article in The New York Times. So Obama decided to make the rebel training programme a “covert action” run by the CIA rather than the Pentagon. He reportedly signed a secret order allowing the agency to begin preparing to train and arm “small groups of rebels in Jordan.” Meanwhile, the Iranian regime continued to step up its military support to the Syrian regime, and Hezbollah Lebanon and Iraqi militias were “taking root” in Syria, as the CIA assessment presented to the President put it.56

In June 2014, Obama claimed that the existence of a moderate Syrian force that was able to defeat al-Assad was “simply not true.” The idea that they would suddenly be able to defeat “not only al-Assad but also highly trained jihadists” if the US “just sent them a few arms” was “a fantasy,” he added.57 In a longer interview in August 2014, Obama defended his position on Syria and repeated his ‘fantasy’ line, adding,

This idea that we could provide some light arms or even more sophisticated arms to what was essentially an opposition made up of former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth, and that they were going to be able to battle not only a well-armed state but also a well-armed state backed by Russia, backed by Iran, a battle-hardened Hezbollah, that was never in the cards.58

Syrian rebels and opposition groups were clearly offended and disappointed by the US President’s remarks. A spokesman for the Syrian opposition’s National Coalition said Obama’s statement was “meant to cover up the inability of his administration to prevent the deterioration of the political and humanitarian situation in the Levant, and to evade the growing criticism to his policies regarding the Syrian crisis.”59

Many also disagreed with the President’s logic, including US presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton. In an interview with The Atlantic in August 2014, she said:

The failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Assad – there were Islamists, there were secularists, there was everything in the middle – the failure to do that left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled.60

Yet, in a speech on 10 September 2014 authorising the expansion of US air strikes against ISIS in Iraq as well as in Syria, Obama called on the Congress to authorise plans to “train and equip Syrian rebels” as part of a four-leg strategy to fight ISIS.61 Suddenly the “former doctors, farmers, pharmacists and so forth” became good enough to be partners in fighting the “highly trained jihadists.” It remains to be seen whether the plan, which will apparently include training camps in Saudi Arabia, will go beyond two previous US promises to arm Syrian rebels and the small-scale, CIA-run training programme in Jordan mentioned above.

Refusing to coordinate with the Assad regime, which “will never regain the legitimacy it has lost,” Obama said that supporting the Syrian opposition was “the best counter-weight to extremists like ISIS.”62 However, this will be done, he added, “while pursuing the political solution necessary to solve Syria’s crisis, once and for all.” (emphasis added)

There was no mention in Obama’s speech of Iran or any of the Iranian-backed militias fighting in Syria. Nothing about the wider wars in Syria and Iraq, in fact. It is likely therefore that the ‘slow bleeding’ policy against Iran and its proxies will continue until further notice.

Indeed, Obama’s different approaches to dealing with ISIS in Syria and in Iraq was a crystallisation of his strategy on Iran. In Iraq, after ISIS took over Mosul in June 2014 and started to advance towards Erbil, Obama was very quick and decisive in authorising air strikes against ISIS forces and positions and in providing the Kurdish armed forces fighting ISIS with all sorts of weapons and support. This gave them significant advantages over the Iranian-back government in Baghdad and the Shia militias controlled by Sepah Pasdaran. In Syria, however, over a year of massacres and military advances by ISIS have not prompted such reactions from the US administration, even though Syrian rebels have been battling ISIS as well as the regime and have been requesting similar assistance from the US and its allies.63

For a few weeks after the start of the US air strikes against ISIS in Iraq, US officials kept repeating that Obama still “did not have a strategy” on dealing with ISIS in Syria and was seeking a broad international coalition before acting. The political circumstances in Syria “are very different,” they added.64 All that is different, in our view, is that Obama appears to be in no rush to put an end to the bloodshed in Syria because it is bleeding Iran and Russia.

Interestingly, the developments in Iraq and the US war on ISIS were seized on by both the Syrian and the Iranian regimes as an opportunity to naturalise their troubled relationship with the US and reach a comprehensive agreement, offering to be part of the new international partnership to ‘fight terrorism’.65 In August 2014, a number of media outlets reported that Iranian Foreign Minister had even offered cooperating with the US in Iraq against ISIS if the sanctions on Iran are lifted.66 But the reports were apparently based on a misquote.67 Iran has always insisted on keeping the two issues separate during the nuclear negotiations.

In any case, the US did not seem interested in such offers, denying any cooperation with Damascus and Tehran.68 President Obama and his team appear to be determined to continue with their ‘slow bleeding’ policy towards Iran and its proxies.

How long can the Iranian regime bleed?

While one may understand the political rationale behind this policy (weakening the Iranian regime and its proxies as much and as long as possible until a confrontation is inevitable), the authors of this report believe that the policy is immoral and politically dangerous, because it is being implemented at the disproportionate expense of the people of Syria and the wider region and because it will inevitably lead to more instability and extremism.

Furthermore, hoping that multiple conflicts or fronts with the Iranian regime, coupled with crippling economic sanctions, would eventually lead to the weakening and even collapse of the regime (i.e. winning the war against the Iranian regime in the streets of Tehran) is, at best, wishful thinking. Similar things were said about the Syrian regime at the beginning of the revolution. Sepah Pasdaran and the Basij have shown that they can and will ruthlessly crush any possible dissent movement inside Iran and that they can ‘bleed’ for much longer, so to speak. In fact, Sepah commanders are now arguably stronger than ever, militarily, politically and economically, not only in Iran but also in the whole Middle East.69

There is no sign that Obama’s ‘slow bleeding’ policy will change in the near future – unless all Syrian opposition groups unite in putting enough pressure on the US administration and its allies to change their position. It is true that Syria has become ‘Iran’s Vietnam’ and that Iran is ‘bleeding in Syria’, but it may be capable of bleeding for a long time to come, much longer than the Syrian people can endure.

Notes & References

1 e.g. ‘Why Syria could turn out to be Iran’s Vietnam – not America’s’, Foreign Policy; ‘Syria’s shadow lurks behind Iran nuclear talks’, Deutsche Welle; ‘Is Syria becoming Iran’s Vietnam?’, War in Context; ‘The consequences of slow bleeding’, Al-Hayat (in Arabic).

Similar analogies have also been made about Hezbollah in Lebanon. e.g. ‘Hezbollah’s ‘Mini-Vietnam’ in Syria worsens on Beirut bombs’, Bloomberg, 6 March 2014.

It should be noted that Naame Shaam was probably the first media outlet to systematically use the term ‘Iran’s Vietnam’ to describe the Iranian regime’s adventure in Syria. See the site-specific search results for the term.

2 For more details on the state of the Syrian economy, see for example: Squandering Humanity: Socioeconomic Monitoring Report o n Syria, UNDP, UNRWA with the Syrian Centre for Policy Research, May 2014; Jihad Yazigi, Syria’s War Economy, European Council on Foreign Relations, April 2014; Mohsin Khan and Svetlana Milbert, ‘Syria’s economic glory days are gone’, Atlantic Council, 3 April 2014.

3 James Hider and Nate Wright, ‘Assad pays snipers “to murder protesters”’, The Times, 26 January 2012.

4 US Department of Treasury, ‘Treasury Sanctions Al-Nusrah Front Leadership in Syria and Militias Supporting the Asad Regime’, 11 December 2012.

5 ‘Confessions of Iraqi mercenaries captured by the rebels in the suburbs of Damascus’ (in Arabic), YouTube, 31 December 2013. See chapter I for more details.

6 Farnaz Fassihi, ‘Iran pays Afghans to fight for Assad’, The Wall Street Journal, 22 May 2014. See chapter I for more details.

7 Geneive Abdo, ‘How Iran keeps Assad in power in Syria’, Foreign Affairs, 25 August 2011.

8 ‘Pictures of Hezbollah fighters killed in Syria’, Naame Shaam, 10 February 2014.

9 Louis Charbonneau, ‘Exclusive: Iran steps up weapons lifeline to Assad’, Reuters, 14 March 2013.

10 See here, for example. See also: ‘Arms transfers to Syria’, SIPRI Yearbook 2013; Jonathan Saul, ‘Exclusive: Russia steps up military lifeline to Syria’s Assad – sources’, Reuters, 17 January 2014.

11 ‘Syria’s Russian weapon buys’, Defense Industry Daily, 29 May 2014.

12 ‘How Putin’s Russia props up Assad’s military’, Channel 4, 10 September 2013.

13 Yves Bourdillon, ‘Téhéran apporte son soutien financier à Damas’, Les Echos, 15 July 2011. For English, see: ‘Tehran ready to give Syria $5.8 billion: report’, Reuters, 15 July 2011.

14 Suleiman Al-Khalidi, ‘Iran grants Syria $3.6 billion credit to buy oil products’, Reuters, 31 July 2013.

15 Michael Peel, ‘Iran, Russia and China prop up Assad economy’, Financial Times, 27 June 2013.

16 Anne Barnard, ‘Syria weighs its tactics as pillars of its economy continue to crumble’, The New York Times, 13 July 2013.

17 Maha El Dahan, ‘Syria issues second food tender using Iranian credit’, Reuters, 24 December 2013.

18 Barbara Surk, ‘Iran sends Syria 30,000 tons of food supplies’, AP, 8 April 2014.

19 Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Statistical Abstract for 2011’ (in Arabic).

20 Julia Payne, ‘Exclusive: Assad’s secret oil lifeline: Iraqi crude from Egypt’, Reuters, 23 December 2013.

21 Jean-Pierre Perrin, ‘Téhéran devient tête de Syrie’, Libération, 25 August 2013.

22 Mohamad Amin, ‘Les dix fardeaux de l’économie en Iran’, Les Echos, 25 April 2014. For an English translation, see here.

23 ‘Military expenditure of Iran’, SIPRI Military Expenditure Database.

24 ‘Are Iranian families earning so little?’ (in Persian), Iranian Economy. See also: ‘Iranian military gets budget increase’, IHS Jane’s 360.

26 See Reuters‘ three-part investigation into SETAD: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.

27 See, for example: Ali Vaez and Karim Sadjadpour, Iran’s Nuclear Odyssey: Costs and Risks, Carnegie, April 2013.

28 David Blair, ‘Sanctions costing Iran $100 million every day’, The Telegraph, 13 Nov 2012. See also this article. There are no relaible official Iranian figures for the impact of the sanctions on the economy because the Iranian government either denies altogether that the sanctions are having any impact on Iran, or they describe the impact in vague terms, such as “high costs”, etc.

29 See here. See also: IMF’s Country Report on Iran, April 2014.

30 ‘How expensive have food items been in Iran in the past five years’ (in Persian), BBC Farsi, 22 March 2014.

31 ‘Ministry of Economy: 31% of families below the poverty line’ (in Persian), TA Bank, 5 July 2014.

32 ‘15 million people below poverty line in Iran – think government incompetence’ (in Persian), Fars News, 5 March 2014.

33 e.g. ‘Iran puts end to economic stagnation: Rouhani’, Press TV, 7 September 2014.

34 See, for example, Ana Maria Luca, ‘The other costs of Hezbollah’s Syrian campaign’, Now, 28 April 2014.

35 Thomas Erdbrink, ‘In Iran, Hopes Fade for Surge in the Economy’, The New York Times, 20 March 2014.

36 Ibid.

37 See, for example, ‘President of the illiterate regrets reading critics’ (in Persian), Fars News, 11 March 2014.

38 ‘Resistance Economy: A model inspired by Islamic economic system and an opportunity to realise an economic epic’ (in Persian), Fars News, 19 February 2014. For English, see: Bijan Khajehpour, ‘Decoding Iran’s ‘resistance economy’’, Al-Monitor, 24 February 2014.

39 ‘Rouhani endorses Ayatollah Khamenei’s ‘resistance economy’’, Iran Pulse, 20 February 2014.

40 ‘Trends of resistance economy to confront the West and the sanctions’ (in Persian), Tasnim News Agency, 28 March 2014.

41 ‘Representative of Supreme Leader in Sepah in Ahwaz: The Iranian nation and leadership are on the side of the oppressed and the barefoot’, Basij Khozestan, 15 March 2014.

42 See here, for example.

43 For Iranian casualties, see: Y. Mansharof, ‘Despite denials by Iranian regime, statements by Majlis member and reports in Iran indicate involvement of Iranian troops in Syria fighting’, The Middle East Media Research Institute, 4 December 2013; Phillip Smyth, ‘Iran’s Losses In the “35th Province” (Syria), Part 1’, Jihadology, 14 June 2013.

For Hezbollah Lebanon’s casualties, see: ‘Pictures of Hezbollah fighters killed in Syria’, Naame Shaam, 10 February 2014; ‘How many Hezbollah fighters have died in Syria?’, Naame Shaam, 16 April 2014.

For a round-up of Iraqi militants killed in Syria in 2013, see this three-part collection by Phillip Smyth on Jihadology: Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.

44 ‘More than 260 thousand killed and died in Syria since the outbreak of the revolution’ (in Arabic), Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, 21 August 2014.

45 ‘Pictures of Hezbollah fighters killed in Syria’, Naame Shaam, idem.

46 See, for example: ‘Hezbollah buries its Syria dead in secret’ (in Arabic), Al-Watan, 12 June 2014.

47 Available here.

48 ‘Posters of Hezbollah’s Syria ‘martyrs’ fill Beirut streets’, Naame Shaam, 29 April 2014.

49 See, for example, here, here and here.

50 ‘Hezbollah’s and regime’s dead in Yabroud number in tens and bodies have not been retrieved yet’ (in Arabic), CNN Arabic, 15 March 2014.

51 ‘Abu Uday: ISIS is selling grains to the regime while people are starving.. and we have infiltrated Hezbollah’ (in Arabic), Al-Hayat, 28 April 2014.

52 Mark Mazzetti, Robert f. Worth and Michael r. Gordon, ‘Obama’s uncertain path amid Syria bloodshed’, The New York Times, 22 October 2013.

53 Jeffrey Goldberg, ‘Obama to Israel — Time is running out’, Bloomberg View, 2 March 2014.

54 Omar Ghabra, ‘Is Washington purposely bleeding Syria?’, The Nation, 25 April 2014.

55 Michael r. Gordon and Mark Landler, ‘Backstage glimpses of Clinton as dogged diplomat, win or lose’, The New York Times, 2 February 2013.

56 ‘Obama’s uncertain path amid Syria bloodshed’, The New York Times, idem.

57 ‘Obama: Notion that Syrian opposition could have overthrown Assad with U.S. arms a “fantasy’’’, CBS News, 20 June 2014.

58 Thomas l. Friedman, ‘Obama on the World’, The New York Times, 8 August 2014.

59 National Coalition of Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, ‘Syrian Coalition: Safi Regrets Obama’s Remarks on Syria’, 23 June 2014.

60 Jeffrey Goldberg, ‘Hillary Clinton: ‘Failure’ to Help Syrian Rebels Led to the Rise of ISIS’, The Atlantic, 10 August 2014.

61 Obama’s speech is available on YouTube. See also here and here.

62 Ibid.

63 See here, for example.

64 See, for example, ‘Obama says strategy not set to strike militants in Syria’, Bloomberg, 29 August 2014.

65 See, for example: ‘Iran ‘backs US military contacts’ to fight Islamic State’, BBC, 5 September 2014; ‘Syria offers to help fight Isis but warns against unilateral air strikes’, The Guardian, 26 August 2014.

66 See, for example, this report and this report.

67 ‘West media spin ‘Iraq’ yarn from Zarif’s remarks on ‘Arak’’, Press TV, 22 August 2014.

68 See, for example: US State Department, ‘Daily Press Briefing’, 21 August 2014. See also: ‘Washington denies cooperation with Tehran in Iraq: Al-Assad is part of the problem not the solution’ (in Arabic), Annahar, 22 August 2014.

69 See, for example, this worrying poll of al-Dahiyeh, Beirut.

English

English  فارسی

فارسی  العربية

العربية