Contents of this chapter:

Contents of this chapter:

What is military occupation?

Does Iranian presence in Syria constitute a military occupation?

From the horse’s mouth

But keep it between us

Case study: Who’s responsible for the death of Al-Manar journalists in Maaloula?

The new command chain

Qassem Soleimani, the de facto ruler of Syria

Case study: Who assassinated the Syrian ‘crisis cell’?

New narrative

Notes & References

II. Syria Under Military Occupation

In February 2013, former Syrian Prime Minister Riad Hijab, who defected from the regime in August 2012, said in an interview with Al-Arabiya TV channel that Syria was currently “occupied by Iran” and was “run” by the commander-in-chief of Sepah Qods, Major-General Qassem Soleimani.1 As far as the authors of this report are aware, Hijab was the first prominent Syrian opposition figure to use the term ‘occupation’ to describe the Iranian regime’s role in Syria, even though Syrian activists and campaigners had been using it rhetorically for a while.2

This chapter will attempt to demonstrate that describing what the Iranian regime is doing in Syria today as an occupation is more than rhetorical; that it actually has a legal basis and legal consequences, including Iran’s obligations as an occupying force in Syria. We will start with a legal discussion of what constitutes a military occupation and whether the Iranian regime’s presence in Syria can be defined as a military occupation. We will then outline various pieces of evidence and case studies to back up this claim, including statements by Iranian officials. Based on this, we will then propose a new narrative about the Syrian revolution and the current situation in Syria, as well as a new set of demands in light of this new reality.

What is military occupation?

In its most basic sense, ‘occupation’ refers to situations where a person or a group of people assume physical control over a place or a piece of land, monopolising the power to enter it, use it and stay there as they please, while excluding others, who may include the original occupants, from doing so. In international humanitarian law, occupation – often referred to in legal jargon as ‘belligerent occupation’ or ‘military occupation’ – is when a state assumes effective, provisional control over a territory belonging to another sovereign state using military force. This control or administration is often referred to as the occupation government or military government, which should be distinguished from martial law, which is the undemocratic rule by domestic armed forces.

There are two main pieces of international law that deal with occupations: the 1907 Hague Regulations Concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land and the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. Article 42 of the Hague Regulations state:

Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.3

Although occupation is not defined as clearly in the Fourth Geneva Convention, Article 2 states:

The present Convention shall apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties [states], even if the state of war is not recognized by one of them. The Convention shall also apply to all cases of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party, even if the said occupation meets with no armed resistance.4

These situations of military occupation are assumed to be temporary, seeking to preserve the status quo pending a final resolution of the conflict. Otherwise they would be considered an annexation of land, colonisation or permanent settlement, which are prohibited under international law, at least in theory. As the 1948 Nuremberg Trial put it, “In belligerent occupation, the occupying power does not hold enemy territory by virtue of any legal right. On the contrary, it merely exercises a precarious and temporary actual control.”5

Nor is it necessary for both parties of the conflict to recognise the occupation or the state of war as such in order for the Fourth Geneva Convention to apply. The main issue is whether the concerned territory (in this case the regime-controlled parts of Syria) is placed “under the authority of the hostile army” (in this case the Iranian armed forces and militias).

The specifics of the nature and extent of this authority have been dealt with in a number of international cases. For instance, in the 2005 case concerning Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that the definition of belligerent occupation as set out in Article 42 of the Hague Regulations required that the authority of the hostile army “was in fact established and exercised by the intervening State in the areas in question.”6 (emphasis added)

It should also be noted that the above treaties – with the exception of Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions – deal with international or inter-state armed conflicts, as opposed to non-international or internal armed conflicts. Thus, if a state intervenes militarily on the side of another state in a non-international armed conflict, it is generally agreed by international law experts that this does not change the qualification of the conflict. However, a non-international armed conflict, even if it was geographically confined to the territory of a single state, can be qualified as international if a foreign state intervenes militarily on the side of rebels fighting against government forces.

In the 1995 case of Tadić, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) concluded that a foreign state exercising “overall control” over a rebel group would be sufficient to internationalise a conflict. This does not require the “issuing of specific orders by the State, or its direction of each individual operation.” It is sufficient that a state “has a role in organizing, coordinating or planning the military actions” of a non-state armed group.7

Furthermore, Article 1 of the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions provides that conflicts shall be qualified as international when they occur between a state and an authority representing a people “fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right of self-determination.”8 The potential application of this provision – which, to our knowledge, has never actually been used before – to the Syrian war will be explored further in the next section.

The legality of conduct during an occupation must be distinguished from the legality of the occupation itself. Thus, once an armed conflict is recognised as international or as a military occupation, the above treaties specify certain rights and duties for the occupying force. These include the protection of civilians, the treatment of prisoners of war, the prohibition of torture, of collective punishment and unnecessary destruction of property, the coordination of relief efforts and so on. The repeated violation of any of these provisions by the occupying force is considered a serious war crime.

For example, Article 43 of the Hague Regulations states:

The authority of the legitimate power having in fact passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.

Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention is more specific:

Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.

Nevertheless, the Occupying Power may undertake total or partial evacuation of a given area if the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand. Such evacuations may not involve the displacement of protected persons outside the bounds of the occupied territory except when for material reasons it is impossible to avoid such displacement. Persons thus evacuated shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased.

The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated.

The Protecting Power shall be informed of any transfers and evacuations as soon as they have taken place.

The Occupying Power shall not detain protected persons in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand.

The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.9

It is worth noting that even if the domestic laws are changed by the occupying force, Article 47 of the Fourth Geneva Convention still guarantees the same rights for the occupied people:

Protected persons who are in occupied territory shall not be deprived, in any case or in any manner whatsoever, of the benefits of the present Convention by any change introduced, as the result of the occupation of a territory, into the institutions or government of the said territory, nor by any agreement concluded between the authorities of the occupied territories and the Occupying Power, nor by any annexation by the latter of the whole or part of the occupied territory.10

Does Iranian presence in Syria constitute a military occupation?

As indicated above, if a state intervenes on the side of another state fighting against domestic rebels, the conflict may still be considered ‘non-international’. However, there is much more to the Iranian intervention in Syria than supporting the Syrian ‘government’ and its armed forces, as the previous chapter has shown.

In addition to arming, training and directing irregular Syrian paramilitary forces (the shabbiha and the NDF) and Iran’s own paramilitary forces fighting in Syria (Sepah Qods and Basij), there are all the Iranian-backed foreign militias that have assumed a leading role in major military operations in certain parts of Syria, at least since the battle of al-Qusayr in Spring 2013. In fact the presence of Hezbollah Lebanon and the Iraqi militias in parts of Syria, such as Sayyida Zaynab and Yabroud, can arguably be considered as a separate occupation of Syrian territory by ‘non-state entities’.

Furthermore, other states (the US, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, etc.) have also intervened in Syria on the side of Syrian rebels. They have all played a role in “organizing, coordinating or planning the military actions of a non-state armed group,” as the judgment in the Tadić case put it. Moreover, the Syria war is no longer geographically confined to the territory of Syria; it has occasionally and increasingly spilled over to other neighbouring countries, especially Lebanon and Iraq. Thus, even if one forgets about the Iranian regime’s involvement, the intervention of other states is arguably sufficient for the Syrian war to be regarded as an international one within the meaning of the Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Some legal experts have argued that if the military intervention by the outside state (in this case Iran) is solely directed at non-state armed groups (the rebels) and their military operations or infrastructure, the conflict should still be regarded as non-international. But as the previous chapter has shown, the Iranian military intervention in Syria (through Iranian weapons, Iranian fighters and military advisors, Iranian-backed militias and so on) has targeted and affected both Syrian civilians and civilian infrastructure. This, according to the experts, renders the conflict into an international one.11 Alternatively, it could be argued that the current war in Syria is both internal and international at the same the time.

A better argument, in our view, is treating the Syrian case as what is sometimes called ‘occupation with an indigenous government in post’.12 Leaving aside the question of Bashar al-Assad’s regime’s legitimacy as an indigenous government,13 and leaving aside the presence of Iranian commanders, fighters and militias on Syrian territory without an official treaty between the two countries allowing the stationing of Iranian armed forces and military bases in Syria, there is abundant evidence that the Iranian regime has established and is exercising authority in Syria, both directly through its armed forces and militias and indirectly through the Syrian regime. The evidence includes new military command structures involving Iranian commanders, fundamental changes introduced into Syrian government institutions as a result of the Iranian regime’s intervention, as well as statements by Iranian officials indicating how they view their role in Syria. The next sections will discuss each of these points in more detail.

There are many examples in history of this type of occupation: Czechoslovakia and Denmark under Nazi-German rule before and during the Second World War, the Soviet and British occupation of Iran in 1941-46, the French mandate in Syria and Lebanon between the two great wars, Vichy France, and even the Syrian occupation of Lebanon up until 2005. In all these cases, the indigenous government was little more than a ‘puppet government’, serving as an agent of the occupying force and effecting the latter’s military control in the concerned state, often against the national interests of that state.

It should also be noted that, even with an indigenous puppet government in place, the implementation of international humanitarian law is still the responsibility of the occupying power.

Finally, as indicated above, the Syrian war could arguably be treated as an international conflict under Article 1 of the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, because it now involves people fighting against the “colonial domination and alien occupation” of the Iranian regime, among others. There is a procedural requirement for this article to be triggered, which involves a recognised authority representing the Syrian people who are struggling for freedom and independence (in this case the Syrian National Coalition or any other Syrian opposition umbrella group) making a formal, unilateral declaration addressed to the Swiss Federal Council. This will trigger the application of the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols to the Syrian opposition’s conflict with the Syrian and Iranian regimes.

One problem here is that Iran has signed but not ratified Protocol 1, which means it is not legally bound by it yet.14 Syria has, however, and both countries are parties to the four Geneva Conventions.15 Moreover, Article 2 common to the four Geneva Conventions provides that, “Although one of the Powers in conflict may not be a party to the present Convention, the Powers who are parties thereto shall remain bound by it in their mutual relations. They shall furthermore be bound by the Convention in relation to the said Power, if the latter accepts and applies the provisions thereof.”16

From the horse’s mouth

As indicated above, it is not necessary for the Iranian government to officially declare or acknowledge that it is in a state of war in Syria or that it is occupying Syrian territory in order for the Hague Regulations and the Fourth Geneva Convention to apply. Nevertheless, various Iranian officials and commanders have actually made such acknowledgements, some of which were cited in the previous chapter.

For example, in August 2012, the commander of Sepah Pasdaran’s Saheb al-Amr unit Gen. Salar Abnoush said in a speech to volunteer trainees: “Today we are involved in fighting every aspect of a war, a military one in Syria as well as a cultural one.”17

In September 2013, the chief of Sepah Qods Gen. Qassem Soleimani told Iran’s Assembly of Experts that Iran “will support Syria to the end.”18

On the same day, 170 members of the Iranian Consultative Assembly (parliament) signed a statement expressing their “support for the resistance front in Syria” and declaring their readiness to “sacrifice our lives beside our Syrian brothers against the infidels and oppressors.”19

Less than two months later, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei echoed Soleimani’s words during a meeting with Syrian religious scholars: “Iran will stand by Syria which is facing an unjust war,” adding that the only way to confront this war was “resistance and steadfastness.”20

Various Iranian officials and commanders have repeatedly stated that Syria was a “red line” or a “strategic defence line” for Iran and that any attack on it would be considered “an attack on Iran.”21 For example, in May 2014, Major-General Yahya Rahim Safavi, the former chief commander of Sepah Pasdaran and Ali Khamenei’s military advisor, said:

Iran’s influence has been extended from [the] Iran, Iraq and Syria axis to the Mediterranean, and this is the third time that Iran’s influence has expanded to the Mediterranean. Our line of defense is no longer in Shalamche [a border town in Iran which was one of the main sites of the Iran-Iraq war]; our defensive lines are [at the] southern Lebanon border with Israel, and our strategic depth has reached areas adjacent to the Mediterranean above Israel.22

The remarks were made during a ceremony held in a Sepah centre in Isfahan to mark the anniversary of the launch of the Beit-ol-Moqaddas operation during the Iran-Iraq war. Safavi also described the previous 40 months of the military and political war in Syria as a “great strategic victory for the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

In February 2013, Hojjat al-Islam Mehdi Taeb, the head of Ayatollah Khamenei’s think-tank Ammar Strategic Base, made a startling statement during a meeting with university student members of the Basij paramilitary force:

Syria is the 35th province of Iran and is a strategic province for us. If the enemy attacks us and wants to appropriate either Syria or Khuzestan [an Arab-populated Iranian province bordering Iraq’s Basra], the priority is that we keep Syria. If we keep Syria, we can get Khuzestan back too. But if we lose Syria, we cannot keep Tehran.23

Other statements by senior Sepah Pasdaran commanders have implied that the Iranian regime was exerting a considerable amount of military authority in Syria. For example, in September 2012, Gen. Qassem Soleimani was quoted by an Iranian nationalist opposition source criticising the Syrian regime’s military strategy and implying that he and his force exerted a considerable amount of influence over it, even though this may ‘go wrong’ sometimes. “We tell al-Assad to send the police to the streets,” he said, “and suddenly he dispatches the army.”24

In April 2014, another senior Sepah commander implied that it was Iranian support that kept Bashar al-Assad in power. “86 world countries stood and said the Syrian government should be changed and Bashar al-Assad should go,” said Brigadier-General Amir Ali Hajizadeh, the commander of Sepah Pasdaran’s Aerospace Force, “but they failed because Iran’s view was to the contrary, and they were eventually defeated.”25

The most direct admission of the Iranian regime’s exercising military authority in Syria came in May 2014 from a very senior Sepah Pasdaran commander, namely Brig. Gen. Hossein Hamedani, who is said to be in charge of overseeing Sepah’s operations in Syria. Bashar al-Assad is “fighting this war [in Syria] as our deputy,” he said, implying that the Iranian regime is the one who is in charge.26 Hamedani also described the Iranian regime’s role in Syria as a “sacred defence” of Iran, a term that was used by the Iranian regime during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war. Urging normal Iranian citizens and businesspeople to support “the troops of Islam and the people of Syria as they did so during the Sacred Defence,” Hamedani also revealed that the Iranian regime was establishing “centres for supporting Syrian people” in various Iranian provinces, where each Iranian province will be “responsible for one Syrian province.”

As pointed out in the previous chapter, all these and other statements and declarations were made by Iranian officials with demonstrable insider knowledge of Iranian military operations. As to why they were made, some appear to have been the result of competing interests or agendas within the Iranian regime (many were immediately removed from the websites that originally published them); others as signals or threatening messages to the outside world. In some cases, thought, they may have simply been out of boasting about the regime’s power and influence in front of regime supporters or the Iranian public more generally.

But keep it between us

Yet, in addition to removing some of these controversial statements, the Iranian regime and/or government have also on occasions reacted with obvious anger and defensiveness. For instance, when Iranian MP Seyyed Mahmoud Nabavian boasted during a speech in February 2014 that Iran had trained some 150,000 Syrian regime fighters on Iranian soil, and another 150,000 in Syria, in addition to 50,000 Hezbollah Lebanon fighters,27 another MP demanded that Nabavian should be prosecuted, adding that disclosing such details paints Iran as a “supporter of terrorists” and would harm the country’s “national interests.”28 But Mansour Haghighatpour, who is affiliated with the ruling conservative bloc, did not deny the Iranian regime’s role in training and supporting Basshar al-Assad’s forces; he only said that revealing such details would harm Iran’s ‘national interests’ and should therefore be kept secret.

Similarly, when Javad Karimi Qodousi, a member of the National Security and Foreign Policy Committee in the Iranian parliament, revealed during a ceremony in November 2013 that there were “hundreds of troops from Iran in Syria” and that what was often reported in the news as Syrian military victories was in fact “the victories of Iran,” the statement was emphatically denied by Sepah Pasdaran, with the force’s spokesperson, Ramazan Sharif, saying: “We strongly deny the existence of Iranian troops in Syria. Iranian [commanders] are only in Syria to exchange experiences and advice, which is central to the defense of this country.” Clearly disturbed by the remarks, he added: “the media in Iran must show greater care when publishing this kind of news so that they do not aid the foreign media’s psychological warfare.”29

Such statements and revelations by Iranian military commanders and other hardliners in Iran were not only embarrassing to Rouhani’s government, which has been marketing itself as more moderate, but also to the Syrian regime, which has been trying hard to maintain an image of a strong, national leadership fighting against a foreign conspiracy aimed at destabilising Syria. The tension reached its height in April 2014, when the Syrian Ministry of Information took unprecedented measures against ‘friendly’ foreign TV channels, including a requirement to obtain a prior permission before covering Syrian regime forces’ battles, especially on the frontlines and in regime-held areas.

The surprise move appears to have been prompted by a number of ‘friendly TV channels’, particularly Hezbollah Lebanon’s Al-Manar and the Iranian-funded Al-Mayadeen, going ‘over the top’ in their celebration of the Syria military victories of Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed militias. The aim of the measures, according to insiders from Al-Manar and Al-Mayadeen, was to allow Syrian state TV to broadcast such ‘scoops’ first so as to give the impression that the Syrian regime was still in control, not Hezbollah and Sepah Pasdaran and the media outlets affiliated with them.30

The affair was neatly summed up in a revealing statement by the Syrian president’s political and media adviser, Buthayna Shaaban:

Some friendly TV channels have recently been broadcasting interviews and reports that kind of give the impression that the Syrian state would not have held up if it was not for so-and-so state and such-and-such party. This is completely unacceptable to us. Syria has held up because of its people, who have so far given over a quarter of a million martyrs. The Ministry of Information has taken a number of measures that reflect the Syrian state’s vision, which sees its relations with other countries as based on mutual respect.

In reaction, Al-Mayadeen decided to significantly reduce its coverage of the war in Syria (or its propaganda, rather).31 Al-Manar managers and Hazbollah commanders were reportedly “very pissed off,” even though they were later reassured that “nothing will change” as Shaaban retracted her statement and the Syrian Minister of Information tried to water down the measures that the ministry had taken.32 It is also plausible that the measures were taken in coordination with the Iranian regime, which had also been trying hard to not be portrayed – at least in front of the outside world – as the one who is actually calling the shots in Syria.

Case study: Who’s responsible for the death of Al-Manar journalists in Maaloula?

On 7 April 2014, three Lebanese journalists working for Hezbollah Lebanon’s Al-Manar TV were killed and two others injured when their car came under gunfire attack in the historic town of Maaloula in Syria. Reporter Hamza Haj Hassan, cameraman Mohammad Mantash and technician Halim Allaw were among a convoy of ‘friendly’ media workers, including some from the Iranian state-run Arabic-speaking channel Al-Alam TV. They were accompanying Syrian regime and Hezbollah forces as these took over Maaloula from opposition forces, along with two other towns in the Qalamon region near the Lebanese border.

Hezbolla Lebanon’s Al-Manar reporter Hamza Haj Hassan, who died in Maloula on 7 April 2014, posing in military uniform and carrying a heavy weapon.

Hezbollah, Iranian and Syrian officials were quick to condemn the “cowardly act” and blame it on “takfiri terrorists.” But important questions remain unanswered.

According to Al-Manar itself, the attack came hours after Syrian regime and Hezbollah forces recaptured Maaloula and drove the opposition forces out. The town was reportedly “under their full control.” So where did these opposition forces that opened fire on the media convoy come from? Why had they not been driven out too?

Haj Hassan’s last Tweet sounded relaxed and confident. He even named the hotel where he and his colleagues were going to stay that day (al-Safir hotel). Would any sensible war correspondent publicly reveal his location if he was not confident that he would be safe there?

These and other facts gave rise to speculation among Syrian and Lebanese commentators that the Hezbollah and Iranian media convoy may have been fired at by angry Syrian soldiers as tensions between the Syrian regime on the one hand and Hezbollah and Sepah Pasdaran on the other reached unprecedented levels in previous days (see above).

A few days before, Syrian soldiers and Hezbollah fighters had been heard exchanging insults on radios and blaming one another for heavy losses, according to sources in the Syrian opposition and the Free Syrian Army. There had even been rumours of tensions at the highest levels between the Syrian and Iranian regimes following statements by Iranian officials that it was Iran that had kept Bashar al-Assad in power.

So could it have been some angry or insulted Syrian soldiers who opened fire on the Hezbollah and Iranian media convoy? Or could it have been orders from higher levels in the Syrian regime to send a message about who’s in charge in Syria?

Even if one ruled out such ‘conspiracy theories’, the Al-Manar journalists were embedded with the Syrian regime and Hezbollah forces, which had launched an offensive to recapture rebel-held towns in the Qalamon region. The TV channel aired footage of two cars, including a white SUV carrying broadcasting equipment for live transmission, riddled with bullets. Moreover, Al-Manar’s director initially said it was “not clear whether the journalists were specifically targeted.” Yet the channel was quick to blame “terrorists” in later reports.

Could it be that the media convoy was simply caught up in crossfire between regime and Hezbollah forces and the remaining opposition fighters on the outskirts of Maaloula, where some reports said the attack took place? It certainly does not look like a targeted sniper attack, as some human rights organisations claimed.

Moreover, Hajj Hassan, along with other Al-Manar reporters, had provided extensive coverage of the Qalamon battles, accompanying Hezbollah and Syrian regime troops, interviewing them and making up stories about their victories and heroism. They were not simply “carrying out their professional duty in covering events,” as some of the condemnations claimed. Al-Manar is a propaganda mouthpiece for Hezbollah Lebanon and the Iranian regime. This has made many in the Syrian opposition armed forces view the channel and its staff as “legitimate military targets.” Indeed, Hajj Hassan had previously posted on Facebook pictures of himself wearing a military uniform and carrying a heavy weapon.33

As a Naame Shaam commentary on the story put it at the time, “All attacks on journalists and media workers covering wars and armed conflicts should be condemned. But watching the prestigious funeral held in South Lebanon for the Al-Manar journalists on Tuesday, and hearing the high-profile, strongly worded condemnations by Lebanese, Syrian and Iranian officials (including the Lebanese president, the Iranian foreign minister and others), one cannot but wonder: where was your conscience when other journalists and media workers were killed in Syria?”34

The new command chain

As with official declarations of war or occupation, there is no legal requirement for a specific number of foreign commanders (in this case Iranian) to be ‘on site’ (in Syria) before it can be said that the country has been placed under a foreign military rule or occupation. Such rule results from the fact that national sovereignty has been surrendered and a foreign military force is now in overall control. To quote Article 43 of the Hague Regulations, it is enough that “the authority of the legitimate power [has] in fact passed into the hands of the occupant.”

The implicit assumption here is that the occupying force exercises this authority directly, through its armed forces, which requires a clear and identifiable command structure. However, as argued above, authority can also be partly exercised indirectly, through local agents or an indigenous government. Evidence suggests that the Syrian case is a combination of both scenarios.

In September 2013, The Wall Street Journal quoted one of the chief commanders of the Free Syrian Army’s intelligence operations, Gen. Yahya Bitar, saying the Free Army possessed identification cards and dog tags of Iranian soldiers the rebels had captured or killed in battle. “Al-Assad asked for them to be on the ground,” he added. “The Iranians are now part of Syria’s command-and-control structure.”35 But is there any other evidence of this apart from claims of Syrian rebels?

The previous chapter cited many examples that clearly show Sepah Pasdaran is in charge of directing the Syrian regime’s overall military strategy, at least in some strategic parts of the country. The military campaigns in al-Qusayr, Yabroud and the wider Qalamon region, which were clearly led by Sepah Pasdaran and Hezbollah, are good examples. Negotiating and brokering the Homs deal in May 2014 on behalf of the Syrian regime is another. Other cases mentioned in the chapter show Iranian commanders are directing military operations on the ground, as the captured footage of the Sepah commander in Aleppo clearly shows. A number of Syrian, Lebanese and Iraqi fighters have also testified to serving under Iranian or Hezbollah command.

A crucial question here is how high up or down the Syria military command chain these Iranian commanders are and whether it is possible to identify a clear Iranian command structure in Syria.36

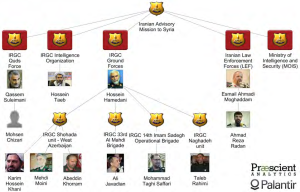

Various reports by Western think-tanks and intelligence services provide varying degrees of details on Iranian military commanders who are said to be directing the Iranian regime’s operations in Syria. For example, a 2013 study by the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project, entitled Iranian Strategy in Syria, claims that Sepah Pasdaran’s Qods Force and elements of the conventional Sepah Pasdaran Ground Forces, as well as several Iranian intelligence agencies, formed a “top-level advisory mission” to support the Syrian regime since early 2011.37 The report names two prominent Sepah commanders, Hossein Hamedani and Qassem Soleimani, as leading this mission, and names a number of other senior commanders from various Sepah units serving under them with specific responsibilities in Syria. Many of these were also mentioned in the previous chapter.

Known senior personnel in Iran’s ‘advisory mission’ to Syria. Source: ‘Iranian Strategy in Syria‘, idem.

Brigadier-General Hossein Hamedani is the former commander of Sepah Pasdaran’s unit in Greater Tehran who led the 2009 crackdown on the Green Movement protesters in Tehran. Before that he served as the commander of Sepah’s units in Kurdistan, where he led the campaign against the guerilla movement there. He is said to be Iran’s main strategist in guerilla and urban warfare and has written a book about that. US and European officials say he is playing “a central role” in implementing similar strategies in Syria.38 As already mentioned in this and the previous chapters, Hamedani has made a number of statements about the Iranian regime’s role in Syria. He was the one who said Bashar al-Assad was fighting the war in Syria as “our deputy.”

Another prominent person in the Iranian regime’s command structure in Syria – and perhaps the most important – is Major-General Qassem Soleimani, the commander-in-chief of Sepah Qods. According to one media report, quoting a Sepah member in Tehran “with knowledge about deployments to Syria,” Soleimani was personally appointed by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to “spearhead military cooperation with al-Assad and his forces.”39 He was indeed one of the first senior Iranian commanders to visit Damascus after the escalation of the war in Syria in late 2011, according to US officials.40

Another report quotes “a prominent Iraqi official who met with Soleimani months ago” saying the latter’s mission in Syria was “not limited to protecting the [Syrian] regime from collapsing [but] also has to preserve Iranian interests in Lebanon and Syria should the regime fall.”41 The same report quotes pro-Iran Iraqis saying, in October 2012, Soleimani “directly took charge of the 70,000 best Syrian fighters, in addition to 2,500 from Hezbollah and 800 Iraqis, most of whom have lived in Syria since the 1980s.”42 More information about Soleimani and his role in Syria is provided in the box below.

Needless to say, the chief commander of Sepah Pasdaran Maj. Gen. Mohamad Ali Jafari and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei should also feature in this command structure.43 Besides the well-known fact that Khamenei has the final say in all important state matters in Iran, there are a number of indications that he has personally been guiding the Iranian regime’s policy in Syria. For instance, in August 2013, the director of Iran’s Central Council of Friday Prayer Leaders in the city of Jiroft in eastern Iran said in a speech that the Supreme Leader was “guiding [the operations] in southern Lebanon and, by virtue of his guidance, Gaza has raised its head and Syria has opposed the infidels.”44

Another indicator is the deployment of members of Iran’s Law Enforcement Forces (LEF) to Syria, which was discussed in the previous chapter. As the above-mentioned report Iranian Strategy in Syria points out, the deployment of LEF personnel in support of the Syrian regime indicates that the Iranian strategy in Syria has been formulated and is being implemented by “the senior-most leadership of Iran.”45 This is because, in theory, LEF falls under the control of the Interior Ministry, which reports to the President. In practice, however, LEF, like all Iranian security services, is overseen by the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), which reports directly to the Supreme Leader. It is therefore very likely, as the report suggests, that the SNSC developed a plan for supporting al-Assad that the Supreme Leader would have personally approved, and that this plan is now being executed. The presence of LEF officers in Syria, the authors add, is “the clearest possible evidence that Iran’s whole-of-government strategy in Syria is being controlled directly by Khamenei rather than Soleimani, the IRGC, or any other single individual or entity in Iran.”46

The authors of this report slightly disagree with the wording: the Iranian strategy in Syria may involve various authorities and departments but is being implemented by the Iranian regime rather than the government, that is, Khameni and Sepah Pasdaran, not Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and his ministers. In February 2014, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif told his American counterpart that he “did not have the authority to discuss or to negotiate on Syria,” suggesting that such powers remained in the hands of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and Gen. Qassem Soleimani.47

Qassem Soleimani, the de facto ruler of Syria

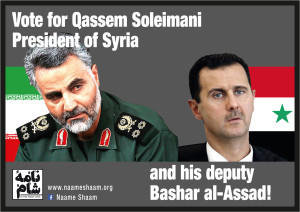

Poster of Naame Shaam’s mock election campaign to vote Qassem Soleimani as president of Syria and Bashar al-Assad as his deputy – May 2014.

In May 2014, shortly before the sham presidential ‘elections’ that were held in Syria on 3 June 2014, Naame Shaam launched a mock ‘election campaign’ calling on Syrians to vote for Gen. Qassem Soleimani as president of Syria and for Bashar al-Assad as his deputy.48 The aim of the campaign was to mock the sham elections and to highlight the Iranian regime’s role in Syria. As the group put it, “if presidential elections are to be forced upon Syrians in regime-held areas on 3 June 2014, why not vote for the one who really has the power and vote for the puppet Bashar al-Assad as his deputy?”

Interestingly, later that month, an Iranian news website quoted al-Assad declaring his ‘love’ for Soleimani during a meeting with Iranian MPs. “Major-General Soleimani has a place in my heart,” he reportedly said. “If he had had to run against me, he would have won the election. This is how much Syrian people love him,” he added.49

Jokes and al-Assad’s unwitty comments aside, Soleimani has been described as the principal Iranian military strategist and “the single most powerful operative in the Middle East today.”

Born in 1957, Qassem Soleimani grew up in the south-eastern Iranian province of Kerman. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, he joined Sepah Pasdaran. A few years later, he joined Sepah Qods, a division of Sepah that conducts special operations abroad in order to “export the Islamic revolution.” He was later promoted to Major General by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The relationship between the two is said to be “very close.”

Early in his career as a guard in his 20s, he was stationed in northwestern Iran and helped crush a Kurdish uprising. He later actively took part in the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq. He spent his early years at Sepah Qods combating Central Asian drugs smugglers and the Taliban in Afghanistan, which provided him with a considerable experience in the inner workings of international trafficking and terrorism networks. He was reportedly one of the principal architects and brains behind restructuring Hezbollah Lebanon in 1980s. He is also said to have been the mastermind behind a bomb plot aimed at killing the Saudi Arabian ambassador to the US in Washington D.C., which later led the US and some EU countries to include him in their sanctions lists.

Between 2004 and 2011, Soleimani was in charge of overseeing Sepah Qods’s efforts to arm and train Shia militias in Iraq in a proxy war against the US. He is reportedly “familiar to every senior Iraqi politician and official.” This provided him with a rich experience, which he would later skilfully apply in Syria. According to media reports, Ayatollah Khamenei personally put him in charge of arming, training and directing the Syrian regime forces and militias, as well as Hezbollah fighters and the Iraqi militias fighting in Syria.50

Another crucial question is who in the Syrian regime and in Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle has been liaising with the Iranian commanders and whether the latter’s involvement resulted in any changes in the Syrian command structure.

The clearest example of fundamental changes in the Syrian command structure and institutions is the creation and rise of the shabbiha. Like the Iranian Basij, the shabbihha were created to substitute the ‘unreliable’ regular army, and have indeed done so. The previous chapter has detailed how this happened and what the Iranian regime’s role was in it. Furthermore, the Syrian army has been literally destroyed by the current ‘internal’ conflict to the extent that it is incapable of defending the country against any outside aggression, as the repeated Israeli attacks on Syrian sites over the past three years have shown.

Another example is the exclusion and inclusion of senior government and army officials in accordance with Iranian desires or orders. The most well-known case is that of Farouq al-Shara’, the former vice-president who has been reportedly under house arrest in Damascus for over a year, after he was prevented from flying to Moscow at the Damascus airport in early 2012. According to one Iraqi politician, quoted by an Arabic media report in February 2014, the reason behind this measure had more to do with the position held by al-Shara’ on Iran’s interference in Syria than his opposition to the military response to the peaceful protests at the beginning of the Syrian revolution, as reports claimed at the time.51 Others claimed he was secretly coordinating with the Russian government to form a ‘national reconciliation government’ that would exclude Bashar al-Assad and his brother Maher.

According to the Iraqi source, al-Shara’ was opposed to Sepah Pasdaran, Hezbollah Lebanon and Iraqi Shia fighters’ being brought in to fight in Syria, because he believed this will encourage other regional powers to interfere in the country and militarise the uprising – which is, indeed, what happened. He was apparently also pushing for a more prominent role for Russia and Saudi Arabia in reaching a political settlement, which the Iranian regime apparently felt would threaten its influence in Syria and limit its own role.

More surprising, perhaps, is the claim that al-Shara’ has been under house arrest not by Syrian police or army but by Sepah Pasdaran. According to the Iraqi source, Sepah commanders asked Bashar al-Assad to guard al-Shara’s two houses in Damascus themselves, because they feared that any Syrian armed forces that guard him, including the elite Republican Guards, who are known to be loyal to al-Assad and his brother Maher, could “collude with him [al-Shara’] and smuggle him out of Syria.”52

These changes in Syrian state institutions resulting from the Iranian regime’s intervention are arguably a grave breach of Article 47 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which provides that people in occupied territory “shall not be deprived, in any case or in any manner whatsoever, of the benefits of the present Convention by any change introduced, as the result of the occupation of a territory, into the institutions or government of the said territory, nor by any agreement concluded between the authorities of the occupied territories and the Occupying Power.”53

Various reports have identified Mohammed Nasif Kheirbek, the former deputy director of Syria’s General Security Directorate and later the vice-president for security affairs, as the main ‘interlocutor’ between the Syrian and the Iranian regimes and the main contact for many Iranian-backed militias.54 A leaked US diplomatic cable described him as Syria’s “point-man for its relationship with Iran.”55 He is said to be the most senior adviser who “has the ear” of Bashar al-Assad, especially since the outbreak of the revolution. In June 2011, Nasif reportedly travelled to Tehran to meet Gen. Qassem Soleimani. They are said to have discussed opening a supply route that would enable Iran to transfer military hardware to Syria via a new military compound at Latakia airport.56

But while Nasif was inherited by Bashar al-Assad from his father and was kept, and even promoted, during the current war, others in the president’s inner circle were not.

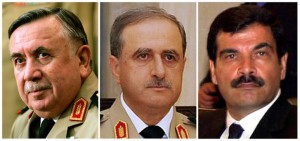

Case study: Who assassinated the Syrian ‘crisis cell’?

Syrian regime’s ‘crisis cell’ officials were allegedly assassinated by Sepah Pasdaran, not by the Syrian opposition, according to Western intelligence sources.

On 18 July 2012, a bomb was allegedly detonated in the National Security HQ in Damascus, killing a number of top military and security officials from what was known as the Syrian regime’s ‘crisis cell’. Those killed included then Defence Minister Dawoud Rajha, his deputy and Bashar al-Assad’s brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, and the Deputy Vice-President Hassan Turkmani. The head of the National Security and al-Assad’s security advisor Hisham Ikhtyar (or Bakhtyar) was seriously injured and was announced dead two days later. Interior Minister Mohammad al-Sha’ar was also injured in the attack.57

Both the Free Syrian Army and what was then known as the Islam Brigade claimed responsibility for the bombing. The FSA’s logistical coordinator Lou’ay al-Moqdad claimed the attack was carried out by a group of FSA members in coordination with some of the officials’ drivers and bodyguards. His claim was even furnished with minute details, such as that two bombs were used, not one, “one hidden in a packet of chocolates and one in a big flower pot.” They had been “planted in the room days before,” he said, and were “remotely detonated by defectors.”58

But a prominent and reliable source in the Syrian opposition told Naame Shaam, quoting a Western intelligence official, that the high-profile operation had nothing to do with the FSA or other opposition armed groups. It was, rether, carried out by Sepah Pasdaran, possibly with direct orders from Gen. Qassem Soleimani himself.

According to the source, some members in the ‘crisis cell’ had opened communications channels with Arab Gulf states and the US with the aim of striking a deal behind Iran’s back. So Sepah Pasdaran struck to prevent such a deal. Since then, President Assad is said to be under Sepah’s fully control, effectively their hostage.

Local residents who live next door to the building also told Naame Shaam’s correspondent in Damascus that they did not hear any explosions on that day, and were “very surprised and bewildered” when they heard the news. The BBC’s correspondent at the time reported that the building’s windows were “not shattered.”59 In an interview the following year, Hisham Ikhtyar’s son, who was present inside the building when the incident took place, said he “felt a shake but did not hear any explosions and did not see any fire. Only the walls fell down and there was darkness.”60

All these pieces of circumstantial evidence suggest that the operation was an inside job. It is possible that the device was small, controlled explosives hidden in the dropped ceiling of the meeting room, as some reports have suggested,61 but this cannot be independently verified without a forensic examination of the site, which has obviously not been possible (the Syrian authorities did not even publish pictures of the crime scene).

Interestingly, the person who is alleged to have planted the bombs is said to be, according to Western intelligence sources, the office manager of Hisham Ikhtyar, who was apparently ‘arrested’ by the Syrian authorities but his whereabouts and fate are unknown to date.

The crucial question is: why were these top officials and commanders assassinated? Some clues may be found in who was present at the meeting and who was not.

A few months before the incident, a civilian secretary who worked for the ‘crisis cell’ defected from the regime and leaked some internal security documents that were made public by Al-Arabiya TV channel.62 The documents reveal the ‘cell’ was headed by Bashar al-Assad himself, who received reports and commented on them before they were discussed by the other officials; his brother Maher, who only attended the cell’s meetings occasionally; and the Vice-Secretary-General of the Ba’th party, Mohammad Saed Bkhaitan, who was later replaced by Hassan Turkmani as the chair of the cell. The other eight members included the four victims of the 18 July operation (Asef Shawkat, Dawoud Rajha, Hisham Ikhtyar and Mohammad al-Sha’ar) as well as the head of the Air Force Intelligence Jamil Hasan, the head of the Military Intelligence Abdul-Fattah Qudsiyyeh, the head of the Political Security Directorate Deeb Zeitoun and the head of the General Intelligence Ali Mamlouk.

According to the leaked documents, these eight members met every day at 7pm (which presumably changed after the documents were leaked). Why were Mamlouk, Hasan, Qudsiyyeh and Zeitoun not present at this meeting?

Western intelligence sources claim that Bashar and Maher al-Assad received intelligence (most probably from the Iranian regime) that the assassinated officials were plotting “an internal coup” in coordination with Russia and/or Gulf countries, which would have removed Bashar and Maher from power and replaced them with a transitional government led by Farouq al-Shara’, aided by a military council headed by Dawoud Rajha and Assef Shawkat. As mentioned above, al-Shara’ has been placed under house arrest and the other two were assassinated in this attack. In December 2012, Mohammad al-Sha’ar escaped what appears to have been another attempted assassination.63

A few days after the ‘crisis cell’ incident, Ali Mamlouk was appointed as the head of National Security, replacing Ikhtyar. Deeb Zeitoun replaced Mamlouk and Abdul-Fattah Qudsiya became Mamlouk’s deputy. Qudsiya was replaced by Ali Younes, who is considered to be one of ‘Maher al-Assad’s men’ within the regime. Finally, Rustum Ghazaleh, the former chief of Syrian intelligence in Lebanon and most recently the head of intelligence in Damascus, took over from Zeitoun. As to Rajha’s Defence Minister post, it was given to Gen. Fahd Jasem al-Freij.64 Apart from the latter, all these men are said to be closer to Bashar and Maher al-Assad than the ones they replaced.

Other indicators may be found in the media coverage of the incident at the time. Iranian media, such as Press TV, were quick to report that Hisham Ikhtyar had been killed, even though he was still in hospital and had not died yet.65 A few days later, when Syrian state media were still saying the attack was carried out by a suicide bomber, Fars News published a report, quoting a Syrian member of parliament, that claimed the Syrian authorities had arrested the person who carried out the ‘bomb attack’, describing him as a security staff member who worked in the same building.66

The ‘crisis cell’ incident was not the first time that the Syrian and Iranian regimes had been accused of orchestrating attacks against Syrian security officials and sites and blaming them on ‘terrorists’. The previous chapter has already mentioned the twin car bomb attacks in May 2012, which killed 55 people outside a military intelligence complex in the Qazzaz area of Damascus. A high-ranking regime defector claimed at the time that the regime was behind this and other apparent suicide bombs.67 Leaked security documents, obtained also by Al-Arabiya in September 2012, seem to back up this claim.68

‘He killed the killed and walked in his funeral’

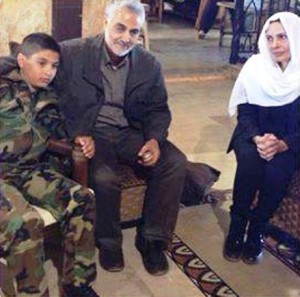

Gen. Qassem Soleimani sitting with Hilal al-Assad’s wife and son in Syria in 2014 (exact date and location unknown).

Another controversial death was that of Hilal al-Assad, a cousin of Bashar al-Assad who was killed in March 2014. Hilal was the notorious chief of the NDF in Latakiya. The Syrian regime and the Free Syrian Army both claimed he was killed by rebels during battles in Kasab that were raging at the time.

But Syrian opposition sources told Naame Shaam at the time that Hilal al-Assad was assassinated by Sepah Pasdaran and/or Hezbollah Lebanon because he had become a “loose cannon” and “was not obeying orders.”69

In May 2014, Al-Arabiyya TV reported that Gen. Qassem Soleimani had made a ‘secret trip’ to Syria to pay tribute to Hilal al-Assad’s family in person.70 A picture showing an ageing Gen. Soleimani sitting with Hilal al-Assad’s wife and son was circulated online without a date or source.

If this turns out to be true, a Syrian proverb sums up the situation pretty well: “He killed the killed and walked in his funeral.”

New narrative

In July 2014, Naame Shaam wrote a long “discussion paper” and sent it to various Syrian and Iranian opposition groups and figures.71 The aim of paper was to “clarify some facts and misconceptions about Iran’s role in Syria and develop a new, joint narrative about the Syrian revolution in light of new realities on the ground.” This chapter has provided further factual and legal bases for some of the relevant points in that paper, namely, those related to the Iranian regime’s occupation of the regime-controlled parts of Syria.

The chapter has argued that the Iranian regime is in overall control of the Syrian regime’s military strategy and that Sepah Pasdaran and their foot soldiers in Hezbollah Lebanon and the Iraqi militias are leading and fighting all major, strategic battles in Syria on behalf of the Syria regime. This, we argued, amounts to surrendering national sovereignty and to a foreign power’s establishing and exercising authority as defined by the Hague Regulations, both directly through its armed forces and militias and indirectly through the Syrian regime.

As the discussion paper put it, “It is no longer accurate to say that al-Assad’s troops are fighting against the rebels with the support of Hezbollah fighters and Sepah Pasdaran ‘advisors’.” It is the other way round and the Assad regime is little more than a puppet government serving the interests of a foreign power (the Iranian regime).

In other words, the war in Syria should be regarded as an international conflict that warrants the application of the four Geneva Conventions and the regime-held areas of Syria should be considered occupied territory – not metaphorically but in the strict legal sense of the word. The de facto rulers of ‘Occupied Syria’ are Gen. Qassem Soleimani and his colleagues in Sepah Qods and Sepah Pasdaran, who dominate the new military command structure in Syria. As indicated above, it does not matter if the Syrian and Iranian regimes deny or refuse to acknowledge this.

The discussion paper urged the Syrian opposition to accept this new reality and adapt its political and communications strategies accordingly. This chapter has also pointed out the possibility of using Article 1 of the 1977 Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, which recognises the struggle of people fighting against “colonial domination and alien occupation” as an international conflict that warrants the application of the four Geneva Conventions.

The right to struggle for liberation from colonial and foreign domination has been recognised by the UN and other international bodies as legitimate. To quote a 1978 UN General Assembly resolution, the Assembly “Reaffirms the legitimacy of the struggle of peoples for independence, territorial integrity, national unity and liberation from colonial and foreign domination and foreign occupation by all available means, particularly armed struggle.”72 The UN General Assembly has even “strongly condemned” governments that “do not recognize the right to self-determination and independence of peoples under colonial and foreign domination and alien subjugation.”73 The authors of this report would argue that the Syrian people’s struggle against the Syrian and Iranian regimes can legitimately be called a liberation struggle.

But this requires the Syrian opposition to unite in its discourse and demands and to act as one recognised representative of the Syrian people fighting against the colonial domination represented by the Syrian and Iranian regimes in Syria. The other legal requirement is that the conduct of the Syrian rebels remains subject to international humanitarian law and excludes terrorist acts, as defined by international law.74

It is the view of the authors that, unless the Syrian opposition united in pushing in this direction, the US and other Western powers are likely to continue with their ‘slow bleeding’ policy towards Iran and not publicly admit that the war in Syria is one against the Iranian regime, not just the Syrian regime, so as to avoid being pressured into taking concrete steps to end the bloodshed in Syria and the wider region. This is the subject of the next chapter.

Recognising the war in Syria as an international conflict that involves a foreign occupation and a people struggling for liberation may also provide another ‘legal weapon’ against the Iranian regime, namely that it is committing “grave breaches” of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which are considered even more serious war crimes than the ones outlined in the previous chapter. This is because, as an occupying force, Iran has certain “duties” towards the Syrian population under its occupation.

There are almost 150 substantive articles in the Fourth Geneva Convention that deal with these duties, including the prohibition of mass deportations and population transfers (Article 49), guaranteeing care and education for children (Article 50), the prohibition of unnecessary destruction of private and public property (Article 53), providing adequate food and medical supplies (Article 55), public health and hygiene (Article 56), religious freedom (Article 58) and so on.

There is abundant evidence – some of which has been outlined in this and the previous chapters – that the Iranian regime and its forces and militias fighting in Syria have repeatedly violated many of these rights since March 2011. For instance, the mass destruction of private and public properties in vast areas of Syria has not always been necessitated by the war (against the rebels) and is a clear and repeated breach of Article 53. Similarly, the mass evacuations of entire villages and districts in Homs and elsewhere, and reports of empty properties being registered to Syrian and Iranian regime supporters from elsewhere (including foreigners such as Afghan fighters) are a clear and repeated breach of Article 49 and may even amount to ethnic cleansing.75

For these and similar arguments to be used, one obviously needs to gather concrete evidence with well-documented cases and examples.76 One should also be careful not to use this sort of arguments in a way that may let the Syrian regime off the hook and blame everything on the Iranian regime.77

Based on this new narrative, the above-mentioned discussion paper also proposed a new set of demands addressed to the US and its allies in the Friends of Syria group, as well as the UN and other international bodies. The main ones relevant to this chapter include demands to support the moderate Syrian rebels with all means necessary to enable them to actually win the war against the Syrian and Iranian regimes, which this chapter has proposed describing as a liberation struggle.

Another relevant demand was linking the Iran nuclear negotiations and sanctions with the Iranian regime’s intervention in Syria and the wider region. As the discussion paper put it, “without direct military intervention [by international forces or Western powers], this represents the only realistic chance of ending the bloodshed in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon at the moment.” Both these and other demands will be fleshed out further in the Recommendations at the end of this report.78

Notes & References

1 ‘Riyad Hijab: Syria in occupied by Iran and is run by Soleimani’ (in Arabic), Al-Arabiya, 14 February 2013.

2 e.g. ‘Syrian protests: “No to Iranian Occupation of Syria”’, Naame Shaam, 17 November 2013.

3 ICRC, ‘Article 42, Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land’, annexed to Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, The Hague, 18 October 1907.

4 ICRC, ‘Article 2’, Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Geneva, 12 August 1949.

5 Cited in Yutaka Arai Takahashi, The Law of Occupation: Continuity and Change of International Humanitarian Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009, p. 7.

6 ICJ, Case Concerning Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo, 19 December 2005, paras.166-180. For more examples of recent case law dealing with the definition of belligerent occupation, see for example: Michael Siegrist, ‘IV. Examples of recent case law dealing with the definition and beginning of belligerent occupation’ in The Functional Beginning of Belligerent Occupation, Graduate Institute Publications, Geneva, 2011.

7 ICTY, ‘Decision on the Defence Motion for Interlocutory Appeal on Jurisdiction’ in Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadić a/k/a “Dule”, 2 October 1995.

8 ICRC, ‘Article 1’, Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977.

9 ICRC, ‘Article 49’, Convention (IV), idem.

10 ICRC, ‘Article 47’, Convention (IV), idem.

11 For a detailed discussion of this point, see: ‘Qualification of armed conflicts’, Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights, 13 June 2012.

12 Adam Roberts, ‘What is a Military Occupation?’, Colombia University, 1985, pp. 284-8. See also: See also: Evan J. Wallach, ‘Belligerent Occupation’ in Interactive Outline Of The Law Of War, 2000.

13 Bashar al-Assad was never democratically elected and his rule is opposed by the majority of Syrians. He literally inherited the presidency from his father, Hafez al-Assad, in 2000. After his father fell ill and his elder brother Basil died in a car accident in 1994, Bashar was brought back from the UK and prepared to succeed his father instead of Basil. In 2000, Bashar was appointed as president by the ruling inner circle after the constitution was hastily changed so as to lower the minimum age for presidency candidates from 40 to 34, which was his age at the time. His ‘re-election’ in June 2014 was viewed by the majority of the world as a ‘cruel joke’. For more details, see here and here.

14 See the list of states party to the Protocol.

15 See the list of states party to the Convention.

16 ICRC, ‘Article 2’, Convention (IV), idem.

17 A copy of the original report in the Iranian Students’ News Agency is available on Daneshjoo. For English, see this WSJ report.

18 ‘Quds Force Commander: Iran to support Syria to the end’, Fars News, 4 September 2013.

19 Ibid.

20 ‘Khamenei: Iran will stand by Syria against the unjust war’, Islamic Awakening, 31 October 2013.

21 See, for example, this collection of official Iranian statements on Syria.

22 ‘Iran’s sphere of influence has been expanded to Mediterranean: general’, Tehran Times, 2 May 2014. See also this report.

23 ‘Head of Ammar Base: Our priority is to keep Syria rather than Khuzestan’, BBC Persian, 14 February 2013. For an English translation, see: ‘Head of Ammar Strategic Base: Syria is Iran’s 35th Province; if we lose Syria we cannot keep Tehran’, Iran Pulse, 14 February 2013.

24 ‘Qassem Suleimani’s criticism of Bashar al-Assad’s policies’ (in Persian), Mazhabi Melli, 5 September 2012.

25 ‘IRGC commander: US-led front unable to topple Assad because of Iran’, Fars News, 12 April 2014.

26 Hamedani’s comments were reported by Iranian state-controlled news agency Fars News on 4 May 2014, but the report was later removed from the agency’s website. A screen shot and an English summary of the report are available here.

27 ‘Nabavian: 300,000 Syrian troops trained by Iran’ (in Persian), Emrooz u Farda. An English report is available here.

28 ‘Vice chair of National Security Committee: Do not speak so other countries say Iran is breeding terrorists’ (in Persian), Khabar Online, 16 February 2014. An English translation and commentary are available here.

29 ‘Sepah denies presence of “hundreds of Iranian troops in Syria”’ (in Persian), Deutsche Welle, 4 November 2013.

30 ‘Syrian regime frustrated by media attributing its ‘victories’ to Hezbollah and other militias’, Naame Shaam, 11 April 2014.

31 Nazeer Rida, ‘Al-Mayadeen channel withdraws Damascus correspondent’, Al-Sharq al-Awsat, 14 April 2014.

32 ‘Buthayna Sha’ban denies statement attributed to her on a Facebook page bearing her name’ (in Arabic), Al-Hayat, 11 April 2014. For English, see ibid.

33 See here.

34 ‘Who’s responsible for the death of Al-Manar journalists in Maaloula? Ayatollah Khamenei’, Naame Shaam, 18 April 2014.

35 Farnaz Fassihi, Jay Solomon and Sam Dagher, ‘Iranians dial up presence in Syria’, The Wall Street Journal, 16 September 2013.

36 For Sepah Pasdaran’s command structure in general, see for example: Will Fulton, The IRGC Command Network: Formal Structures and Informal Influence, AEI’s Critical Threats Project, July 2013.

37 Will Fulton, Joseph Holliday and Sam Wyer, Iranian Strategy in Syria, AEI’s Critical Threats Project and Institute for the Study of War, May 2013.

38 Farnaz Fassihi and Jay Solomon, ‘Top Iranian official acknowledges Syria role’, The Wall Street Journal, 16 September 2012.

39 Farnaz Fassihi, ‘Iran said to send troops to Bolster Syria’, The Wall Street Journal, 27 August 2012.

40 ‘US: Iran supplying weapons for Syrian crackdown’, Now, 14 January 2012.

41 Mushreq Abbas, ‘Iran’s man in Iraq and Syria’, Al-Monitor, 12 March 2013.

42 Ibid.

43 For more details about the Iranian decision-making structure under Khamenei, see, for example: Frederick W. Kagan, Khamenei’s Team of Rivals: Iranian Decision-Making, American Enterprise Institute, July 2014.

44 ‘Iranian religious leader: Syria, Gaza and South Lebanon in the hands of Khamenei’ (in Arabic), Al-Arabiya, 20 August 2013. For English, see: Y. Mansharof, ‘Despite denials by Iranian regime, statements by Majlis member and reports in Iran indicate involvement of Iranian troops in Syria fighting’, The Middle East Media Research Institute, 4 December 2013.

45 Will Fulton et. al., idem.

46 Ibid.

47 ‘Zarif tells Kerry he can’t talk Syria (See Pasdaran)’, Iran Times, 21 February 2014. See also, ‘FT interviews: Hassan Rouhani’, Financial Times, 29 November 2013.

48 ‘Election campaign: #Vote_for_Qassem_Soleimani president of Syria!’, Naame Shaam, 22 May 2014. As part of the campaign, Naame Shaam also called for ‘election rallies’ at Iranian embassies and consulates around the world on 2 June 2014. See here.

49 ‘Interesting comments by Bashar al-Assad about General Soleimani’ (in Persian), Khedmat, 24 June 2014. For an English translations, see here.

50 For more on information on Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, see, for example: ‘Iran’s Master of Iraq Chaos Still Vexes U.S.’, The New York Times, 2 October 2012; ‘The Shadow Commander’, The New Yorker, 30 September 2013; ‘Qassem Suleimani: the Iranian general ‘secretly running’ Iraq’, The Guardian, 28 July 2011; ‘Qassim Suleimani: commander of Quds force, puppeteer of the Middle East’, The Guardian, 16 June 2014; ‘Iran’s Man in Iraq and Syria’, Al-Monitor, 12 March 2013.

51 ‘Al-Shara’ banned from leaving Damascus and the [Iranian] Revolutionary Guards are in charge of guarding him’, Al-Seyassah, 12 February 2014. For English, see here. See also: Bassam Barabandi and Tyler Jess Thompson, ‘A Friend of my Father: Iran’s Manipulation of Bashar al-Assad’, Atlantic Council, 28 August 2014.

52 Ibid.

53 ICRC, ‘Article 47’, Convention (IV), idem.

54 ‘Factbox: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle’, Reuters, 4 May 2011.

55 ‘Treasury Team’s Damascus consultations on financial sanctions’, Cable ID: 07DAMASCUS269_a, WikiLeaks, 15 March 2007.

56 ‘Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle’, BBC, 30 July 2012.

57 See, for example, ‘Damascus blast ‘kills’ top Assad officials’, Al-Jazeera, 19 Jul 2012; ‘Syria attack: Security chief Ikhtiar dies from wounds’, BBC, 20 July 2012.

58 ‘Syria: Fresh fighting in capital as hundreds flee regime reprisal attacks’, The Telegraph, 19 July 2012.

59 ‘Top Syrian security officials killed in suicide bomb’ (in Arabic), BBC, 18 July 2012.

60 ‘Son of Gen. Bakhtyar tells Asia [news agency] the details of his father’s assassination’ (in Arabic), YouTube, 10 November 2013. For text (in Arabic) see here.

61 Nizar Nayouf, ‘Where have Bashar al-Assad and his brother hidden the perpetrator of the crime, the office manager of Hisham Ikhtiar’ (in Arabic), 19 July 2013. See also: ‘A Friend of my Father’, idem.

62 ‘Al-Arabiya reveals leaked documents about the Syrian crisis cell’ (in Arabic), Al-Arabiya, 17 April 2012.

63 ‘Syrian interior minister in Beirut for treatment’, Al-Arabiya, 19 December 2012.

64 ‘Assad names new security chief after bombing’, Reuters, 24 July 2012.

65 ‘Damascus blast: More than meets the eye’, Press TV, 19 July 2012. The report appears to have been removed since.

66 The report was picked up by various international media. See, for example, ‘Syria says arrests person responsible for

Damascus bombing’, Reuters, 24 July 2012.

67 Ruth Sherlock, ‘Exclusive interview: Why I defected from Bashar al-Assad’s regime, by former diplomat Nawaf Fares’, The Sunday Telegraph, 14 Jul 2012.

68 ‘Assad’s regime carried out deadly Damascus bombings: leaked files’, Al-Arabiya, 30 September 2012.

69 ‘As part of his Syria ‘election campaign’ tour: Qassem Soleimani visits family of killed Syrian shabbiha commander Hilal al-Assad’, Naame Shaam, 29 May 2014.

70 ‘Sepah Qods chief visits Hilal al-Assad’s family in Damascus in secret’ (in Arabic), Al-Arabiya, 24 May 2014.

71 The paper has not been published as it was intended for internal discussion among Syrian and Iranian opposition groups. However, a brief summary of some of the relevant points can be found in another, open appeal by Naame Shaam addressed to opposition groups and activists in Syria and Iran: ‘Syria is an occupied country and Sepah Pasdaran are the ones who rule it’, Naame Shaam, 9 May 2014.

72 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution A/RES/33/24, 29 November 1978.

73 United Nations General Assembly, Resolution A/RES/3246 (XXIX), 29 November 1974.

74 For a legal discussion of the difference between legitimate armed struggle and terrorism, see, for example: John Sigler, ‘Palestine: Legitimate Armed Resistance vs. Terrorism’, The Electronic Intifada, 17 May 2004.

75 See, for example: ‘After Assad’s New Regulations.. Who Acquires Syrians Houses?’, Syrian Economic Forum, 28 August 28 2014.

76 Various Syrian and international human rights organisations and NGOs are already doing this work and can be contacted for help.

77 For an example of how these arguments may be used, see: ‘Israel’s obligations as an occupying power under international law, its violations and implications for EU policy’, European Coordination of Committees and Associations for Palestine, 29 January 2014.

78 Some of the demands can be found in this open letter by Naame Shaam to the E3+3 powers negotiating with Iran about its nuclear programme: ‘Open letter to foreign ministers: Link nuclear talks with Iran’s role in Sryia, Iraq and Lebanon’, Naame Shaam, 6 July 2014.

English

English  فارسی

فارسی  العربية

العربية