3. ‘Urban planning’

In September 2012, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad issued a presidential decree authorising the creation of two urban planning zones within the governorate of Damascus as part of a “general plan for the city of Damascus to develop the areas of unauthorised residential housing [slums].”1 The first zone is situated in the south-east of al-Mazzeh, encompassing the real estate departments of al-Mazzeh and Kafarsouseh. The second stretches south of the Southern Highway, encompassing the departments of al-Mazzeh, Kafarsouseh, Qanawat, Basateen, Darayya and Qadam.

The decree prohibited the trading in any property within these zones or authorising any new construction projects. It also required the City Council to put together a list of all the property owners in these areas within a month, and required all property owners in the area to publicly declare their ownership of their properties and gave them a choice of selling their stakes in the property. The decisions of the “committee of experts” created by the decree were to be “final and unappealable.”

Commenting on the decree, the Minister of Local Administration Ibrahim Ghalawanji said Decree 66 “came as a response to the government’s priorities and its vision for overcoming the repercussions of the crisis that Syria is going through, and as a first step in the reconstruction of illegal housing areas, especially those targeted by armed terrorist groups, through rebuilding those areas to high development standards…”2

Daraya, Moadamiya and other towns in this part of the Damascus countryside were strong revolution hotbeds and, later, armed opposition strongholds. Like in other parts of Syria, initial peaceful protests turned into armed opposition and many Free Syrian Army fighters used bases in the area to stage attacks on government targets, including the Mazzeh military airport and regime checkpoints. In August 2012, regime forces launched a massive offensive against the two towns. The offensive was one of the deadliest regime attacks up until that point. This was followed by another offensive in December 2012, following an opposition attack on a regime checkpoint on 25 November.

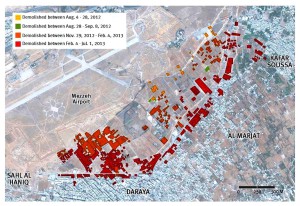

Demolitions around Mezzeh airport, Damascus. Dates of demolition: August 2012 and December 2012-March 2013. Estimated demolished area: 41.6 hectares.

Source: Human Rights Watch Report “Razed to the Ground – Syria’s Unlawful Neighborhood Demolitions in 2012-2013”, January 2014.

The Mazzeh destruction and subsequent demolitions were therefore clearly linked to the armed conflict. Indeed, when asked by the Wall Street Journal about the motives behind the demolitions, Hussein Makhlouf, the governor of the Damascus Countryside and a relative of al-Assad, said they were “essential to drive out terrorists.”3

According to HRW’s satellite images, a total of 41.6 hectares of buildings was demolished around the Mazzeh military airport, mainly between December 2012 and July 2013. This is arguably widespread and systematic enough to satisfy the requirements of the war crime of unlawful destruction of civilian property. And it was clearly part of a state policy, as indicated by the presidential decree.

However, to say that the Mazzeh demolitions may have been militarily justified by the armed opposition’s attacks on regime targets, even if the demolitions were excessive and disproportionate, seems to miss another, important part of the story, namely, that there had already been plans to ‘reconstruct’ the whole area well before the current conflict started. And the Iranian embassy in Damascus, which is located on al-Mazzeh Highway and is within the area designated by Decree 66, appears to be at the heart of this plan.

It is widely known that, back in 1991, former Syrian President Hafez al-Assad ordered the Damascus City Council to scrap law no. 60 concerning seven real estate departments in al-Mazzeh which had been appropriated by the Council. The ownership was transferred to members of the Assad family. The land was subsequently ‘given’ to the Iranian embassy in Damascus, and it is there that the new embassy building was built.

Syrian opposition sources claim the operation was overseen by the then head of the Permits Department within the Damascus Council, Bassam Kheirbek, the nephew of Mohammad Nasif Kheibek.4 The latter was the former deputy director of Syria’s General Security Directorate and later the vice-president for security affairs. Mohammad Nasif Kheibek is known to have been the main ‘interlocutor’ between the Syrian and the Iranian regimes and the main contact for many Iranian-backed militias.5 A leaked US diplomatic cable described him as Syria’s “point-man for its relationship with Iran.”6 Later on, the sources claim, an engineer called Ahmad al-Dali, the head of the Antiques Department in the Council, was tasked with purchasing properties around the new embassy building, behind al-Razi hospital, on behalf of the embassy (more on this below).

The demolitions in al-Mazzeh appear to be a continuation of a long-standing plan of creating an ‘Iranian zone’ in al-Mazzeh similar to the Hezbollah stronghold in the southern suburb of Beirut (al-Dahiyyeh). The plan was simply accelerated because of or under the cover of the war.

It is also worth noting that the strategic road going from southern Damascus to Lebanon (al-Mutahalleq al-Janoubi, the city’s southern motorway) goes right through the area designated by Decree 66. Since the UN Security Council Resolution 1701 of 2006 stopped arms shipments via Lebanese ports, all Iranian arms shipments to Hezbollah Lebanon go through land routes in Syria.

Similar stories were repeated in other strategic areas across the country, such as Homs. In June 2014, the governor of Homs, Talal al-Barazi, discussed with members of the Homs City Council a proposed project to “reconstruct the neighborhoods of Baba Amr, al-Sultaniyeh and Jobar.”7 During the “exceptional session,” the governor pointed out the Council’s intention to cancel decree no. 26 concerning the Baba Amr neighborhood and to “include it in decree no. 66.” The project was reportedly proposed by Dr. Mzahem Zain-Eddin, the Dean of the Faculty of Architecture.8 Baba Amr had seen some of the fiercest fighting and deadliest sieges by Syrian regime and Hezbollah forces in 2012 and 2013.9

In addition to the unlawful, wanton destruction of civilian property, these urban planning schemes arguably amount to an unlawful appropriation of civilian property not justified by military necessity, even though they took place in the context of the armed conflict. Both the designers of these schemes and those who ordered and carried them out must have been aware of this context.

Moreover, the schemes were extensive and systematic and appear to have been carried out wantonly, even though both their designers and those who ordered and carried them out must have been aware that the properties and their owners were protected under domestic and international law, as evidenced by the fraudulent or violent means with which they were implemented (the following section will shed more light on this).

Finally, various Iranian officials appear to be implicated in these schemes, including the Iranian ambassador to Syria, the Iranian mediator in Homs known as Haji Fadi, Iranian businessmen and Sepah Pasdaran commanders with responsibilities Syria.

Notes & References:

1. The full text of Decree 66 of 2012 is available here (in Arabic).

2. Ibid.

3. Available here.

4. Note posted by Dr Zakwan Baaj, from Syria Freemen Conference, on his personal Facebook page, 5 February 2015, based on information leaked from the inside the City Council. Available here (in Arabic).

5. ‘Factbox: Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s inner circle’, Reuters, 4 May 2011, available here.

6. ‘Treasury Team’s Damascus consultations on financial sanctions’, Cable ID: 07DAMASCUS269_a, Wikileaks, 15 March 2007, available here.

7. ‘Homs Governorate discusses reconstruction of Baba Amro neighborhood’, SANA, 1 July 2014, available here.

8. Ibid.

9. For more on the fighting in Homs and the strategic importance of this city for Hezbollah Lebanon and the Iranian regime, see here.

English

English  فارسی

فارسی  العربية

العربية